Timeline

June 1944.

1944-06-01-Thursday

1944-06-02-Friday

1944-06-03-Saturday

1944-06-04-Sunday

1944-06-05-Monday

Eisenhower makes the go/no-go decision in marginal weather; he gives the go-ahead for the 6 June assault. (Levine, 2007, 33).

1944-06-06-Tuesday

Normandy Campaign. 6 June to 24 July 1944

Operation Neptune was the codename given to the naval operation to transport and land the forces ashore, and Operation Overlord referred to the subsequent campaign on the ground (Hart, The D‑Day Landings, 2004, p. 2).

D-Day: Airborne spearhead

The 82nd Airborne Division and 101st Airborne Division drop across the Cotentin to secure causeways, bridges, and key road hubs such as Sainte-Mère-Église, screening Utah Beach’s exits and disrupting German response.

Mission Boston (Airborne)

Cotentin Peninsula, Merderet River, Normandy, France: night parachute assault by MG Matthew Ridgway’s U.S. 82nd Airborne; ~6,420 paratroopers from nearly 370 C-47s dropped into ~10 sq mi DZs on both sides of the Merderet, ~5 hours before the beach landings; component of Operation Neptune (Overlord). Source: Wikipedia.

Mission Albany (Airborne)

Cotentin Peninsula, SE corner, Normandy, France: night parachute assault by the U.S. 101st Airborne; ~6,928 paratroopers from 443 C-47s dropped ~5 hours before the beach landings; intended ~15 sq mi DZs but scattered over ~2× that area (some sticks ~20 miles off); most objectives taken on D-Day, four days to consolidate; mission: secure VII Corps’ left flank/rear; later reinforced by ~2,300 glider infantry landed by sea. Source: Wikipedia.

Mission Chicago (glider)

Pre-dawn glider reinforcement for the U.S. 101st Airborne on 6 June 1944, part of Operation Neptune Overlord; originally planned as the main 101st assault but executed after Mission Albany; limited in scale due to proximity to Utah Beach with most support units arriving by sea. Source: Wikipedia.

Mission Detroit (glider)

Pre-dawn glider reinforcement for the U.S. 82nd Airborne on 6 June 1944, part of Operation Neptune Overlord; executed after Mission Boston; landing zone near Sainte-Mère-Église west of Utah Beach. Source: Wikipedia.

Mission Elmira (glider)

Evening 6 June 1944 delivery of major 82nd Airborne reinforcements as part of Operation Neptune Overlord; 176 C-47 tugs with 36 Waco CG-4 and 140 Airspeed Horsa gliders; aimed at LZ W two miles southeast of Sainte-Mère-Église with overflow to DZ O; key cargo included two glider artillery battalions and 24 howitzers; arrivals in four serials with two delayed until near sunset. Source: Wikipedia.

Mission Keokuk (glider)

Evening 6 June 1944 glider reinforcement for the U.S. 101st Airborne following Missions Albany and Chicago; landing on an LZ northwest of Hiesville co-located with DZ C to speed reinforcement of division drop zones; 32 Horsa gliders towed by 434th Troop Carrier Group C-47s; 157 personnel from signal medical and command units plus 40 vehicles 19 tons of equipment and 6 anti-tank guns. Source: Wikipedia.

D-Day: Seaborne landings

D-Day: seaborne landings after dawn across Utah Beach, Omaha Beach, Gold, Juno, Sword. (Levine, 2007, 33–34).

6th Airborne takes the Orne & Caen Canal bridges; Merville battery attack begins; scattered U.S. drops work to secure exits for Utah Beach. (Levine, 2007, 34).

U.S. V Corps assaults Omaha Beach; VII Corps lands at Utah Beach. Rangers scale Pointe du Hoc to neutralize the battery threatening both beaches. By nightfall, U.S. beachheads are established despite very heavy fighting, especially on Omaha Beach. Naval gunfire, engineers, and small-unit leadership are decisive. (U.S. Army Center of Military History; Naval History and Heritage Command).

Airborne operations begin over Normandy in advance of the main landings.

82nd and 101st U.S. Airborne Divisions are dropped into the Cotentin Peninsula.

6th British Airborne Brigade is dropped east of the River Orne to secure bridges and neutralize German defenses. (Bishop 2003).

06:30

U.S. forces make the first seaborne assaults on the beaches codenamed Utah and Omaha. Casualties are heavy at Omaha, but Utah and other sectors progress steadily. (Bishop 2003).

07:25

British and Canadian forces assault Gold and Sword beaches. Despite heavy resistance, they secure beachheads, though German counterattacks continue. (Bishop 2003).

07:55

Canadian 3rd Infantry Division and armor land at Juno Beach. Troops advance inland under fire, gradually expanding the beachhead. (Bishop 2003).

10:00

British advance out from Gold Beach takes La Rivière. (Bishop 2003).

11:00

Bernières is taken by Canadian forces advancing from Juno Beach. (Bishop 2003).

12:00

U.S. 4th Infantry Division pushes inland from Utah Beach and links with 101st Airborne Division paratroopers. (Bishop 2003).

13:00

British and French commandos landing at Sword link up with airborne troops holding bridges over the Orne. (Bishop 2003).

16:00-20:00

German 21st Panzer Division counterattacks toward Sword Beach but is stopped by Allied naval and air power. Canadian 3rd Infantry Division advances inland with the British 50th Division from Gold Beach, consolidating the largest Allied beachhead of D-Day. (Bishop 2003).

24:00

D-Day concludes with varied gains. Allies establish beachheads up to 16 km (10 miles) deep and 96 km (60 miles) long, but with high casualties (12,000 Allied troops). (Bishop 2003).

1944-06-07-Wednesday

Lodgments expand; Sainte-Mère-Église is held; link-ups between airborne and seaborne forces solidify Utah Beach exits. (Ibiblio).

1944-06-08-Thursday

Continued consolidation of U.S. lodgments inland from Utah Beach and Omaha Beach. (Ibiblio).

U.S. V Corps links up with the British, connecting the beachheads near Bayeux. (Levine, 2007, 62).

1944-06-09-Friday

1944-06-10-Saturday

Battle of Carentan begins. The 101st Airborne fights toward the town to close the gap between Omaha Beach and Utah Beach. (National WWII Museum).

1944-06-11-Sunday

Carentan captured by U.S. forces, closing the gap between Utah Beach and Omaha Beach. (Levine, 2007, 62).

1944-06-12-Monday

Carentan falls; U.S. forces beat back German counterattacks at “Bloody Gulch” with 2nd Armored support. (National WWII Museum).

1944-06-13-Tuesday

At Villers-Bocage, 7th Armoured’s thrust is checked by Wittmann’s Tigers. (Levine, 2007, 62).

1944-06-14-Wednesday

RAF heavies use Tallboy bombs against E-boat pens at Le Havre and Boulogne. (Levine, 2007, 64).

1944-06-15-Thursday

Continuation of RAF Tallboy raids on Le Havre and Boulogne. (Levine, 2007, 64).

1944-06-16-Friday

1944-06-17-Saturday

1944-06-18-Sunday

U.S. VII Corps reaches Barneville, cutting the Cotentin; the “great storm” shortly after devastates shipping and later wrecks Mulberry A. (Levine, 2007, 65–66).

1944-06-19-Monday

The “great storm” strikes the Channel. American Mulberry harbor off Omaha Beach is wrecked. (Naval History and Heritage Command).

1944-06-20-Tuesday

1944-06-21-Wednesday

1944-06-22-Thursday

Drive on Cherbourg begins as VII Corps (4th, 9th, 79th IDs, later 90th) attacks the peninsula. (U.S. Army Center of Military History).

VII Corps opens its attack on the Cherbourg outer perimeter with heavy air support. (Levine, 2007, 66).

1944-06-23-Friday

1944-06-24-Saturday

1944-06-25-Sunday

1944-06-26-Monday

Fall of Cherbourg: von Schlieben gives up on the 26th; pockets hold out to the 29th. (Levine, 2007, 66).

1944-06-27-Tuesday

Cherbourg surrenders, securing a major port for the U.S. build-up. (U.S. Army Center of Military History).

1944-06-28-Wednesday

British take Hill 112 during Operation Epsom. (Levine, 2007, 68).

1944-06-29-Thursday

1944-06-30-Friday

—

July 1944

St-Lô, Goodwood, Cobra

1944-07-01-Saturday

1944-07-02-Sunday

1944-07-03-Monday

Field Marshal Günther von Kluge replaces Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt as German Commander in Chief West. (Williams 1960, 223)

U.S. First Army opens its general offensive “Battle of the Hedgerows” on the western flank. (Williams 1960, 223)

Battle of La Haye-du-Puits

VIII Corps attacks south down the west coast of the Cotentin toward La Haye-du-Puits with the 79th Infantry Division, 82nd Airborne Division, and 90th Infantry Division abreast; progress is limited by hedgerows, but the 82nd Airborne Division gains Hill 131 northeast of the town. (Williams 1960, 223)

Hill 131

Heavy rain cancels air support; at 05:15 artillery opens and VIII Corps attacks—82nd Airborne Division seizes Hill 131 while 79th-Infantry-Division and 90th-Infantry-Division push toward Montgardon and Mont Castre. (Wikipedia: Battle of La Haye-du-Puits).

U.S. forces begin sequential attacks south of the Vire as the St-Lô battle builds. (Levine, 2007, 70).

90ID #79ID

1944-07-04-Tuesday

Hill 95

U.S. First Army: VIII Corps continues slow progress south on the western flank. 82nd Airborne Division takes Hill 95, overlooking La Haye-du-Puits from the northeast, where it remains until pinched out by the 79th and 90th Divisions.

VII Corps opens an attack east of VIII Corps, between the swamps of the Prairies Marcagéuses and the Taute River. The 83rd Division, in its first action, advances toward Périers but meets firm resistance.

British Second Army: In I Corps, the Canadian 3rd Division seizes Carpiquet but is held up short of its airfield. In VIII Corps, 43rd Division attacks northeast astride the Odon to ease pressure on I Corps. (Williams, 1960, 226).

Hill 121

By 08:30 the 79th Division secures Hill 121, gaining observation over Montgardon ridge and La Haye-du-Puits, but advances halt short of the town under heavy fire. (Wikipedia: Battle of La Haye-du-Puits).

1944-07-05-Wednesday

79th Division reaches the slopes of Montgardon; 3/314th briefly enters La Haye-du-Puits and captures the rail station before pulling out under artillery; a flanking attempt bogs in the swamps. (Wikipedia: Battle of La Haye-du-Puits).

U.S. First Army: 35th Division begins landing in Normandy. VIII Corps overruns the rail stations of La Haye-du-Puits. VII Corps continues its slow advance toward Périers. (Williams, 1960, 226).

1944-07-06-Thursday

A break in the weather allows close air support, but rain returns in the evening as the 90th Division shifts weight to support the 359th near Mont Castre. (Wikipedia: Battle of La Haye-du-Puits).

U.S. Third Army establishes headquarters in France at Nehou, with VIII, XII, XV, and XX Corps assigned (though VIII remains with First Army).

U.S. First Army: VIII Corps closes in on La Haye-du-Puits, nearly enveloping the town against stubborn German resistance. VII Corps commits the 4th Division west of the 83rd as the attack on Périers continues under heavy opposition. (Williams, 1960, 226).

1944-07-07-Friday

RAF Bomber Command conducts heavy night raids (7–8 July), dropping 2,662 tons on military targets in preparation for the assault on Caen.

U.S. First Army: VIII Corps—79th and 90th Divisions continue attacking German positions in the La Haye-du-Puits–Mont Castre Forest area, repelling counterattacks. VII Corps makes limited gains down the Carentan–Périers road. XIX Corps opens its offensive with the 30th Division, establishing a bridgehead in the St. Jean-de-Daye area.

- 117th Infantry crosses the Vire at 0430.

- 120th Infantry attacks across the Vire–Taute Canal at 1345.

After nightfall, CCB/3rd Armored Division crosses into the bridgehead at Airel, tasked to expand toward St. Gilles; 113th Cavalry Group moves up on the division’s right. (Williams, 1960, 226).

Caen

British forces renew their attempt to take Caen, this time after the town has been carpet-bombed by the RAF. (Bishop 2003).

Hill 84

With the ridge line held, 1/314th’s attempt to occupy La Haye-du-Puits is repulsed; a strong German counterattack nearly forces 79th off Hill 84 before withdrawing after tank losses; the division suffers over 1,000 casualties. (Wikipedia: Battle of La Haye-du-Puits).

Caen (most of it) taken by direct attack after heavy bombing. (Levine, 2007, 68).

#### 1944-07-08-Saturday

2/314th, with tanks and M10s, fights house-to-house into La Haye-du-Puits; Germans fall back to the rail yards and the town is captured—Lt. Arch B. Hoge Jr. raises a Confederate flag; 2/314th later receives a Presidential Unit Citation. (Wikipedia: Battle of La Haye-du-Puits).

U.S. First Army: VIII Corps—79th Division overruns La Haye-du-Puits; 8th Division enters line between 79th and 90th. VII Corps continues attacks down the Carentan–Périers road.

XIX Corps expands its bridgehead despite difficulty coordinating infantry and armor.

- 113th Cavalry Group overruns Goucherie and Le Mesnil-Véneron; late in day attached to CCA/3rd Armored Division, pushing toward Le Désert.

- 30th Division advances toward Le Désert and Cavigny (120th Infantry right, 117th center, 119th left).

- CCB/3rd Armored Division reaches near La Bernardrie, attached to 30th late in day.

- 35th Division completes landing and is attached to XIX Corps.

British Second Army: I Corps opens assault on Caen at 0420 with Canadian 3rd Division (right), 59th (center), 3rd (left). British troops penetrate into northeast Caen with close support from U.S. heavy bombers. (Williams, 1960, 226).

1944-07-09-Sunday

79th Division resumes its advance at noon; 315th attacks Hill 84’s southern slopes and secures the objective by 13:00, beating back a counterattack that evening. (Wikipedia: Battle of La Haye-du-Puits).

2nd SS Panzer counterattacks against U.S. 3rd Armored on the Vire. (Levine, 2007, 70).

1944-07-10-Monday

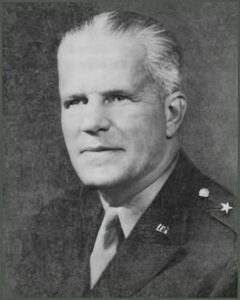

Brig. Gen. Walker, Nelson M (Assistant Division Commander of the 8th Infantry Division) is killed while organizing an assault; 90th Division’s 358th attacks Mont Castre; German command authorizes withdrawal to the Ay and Sèves; 79th’s 313th takes Le Bot after an accidental short airstrike enables capture of the Hierville–Angoville-sur-Ay area. (Wikipedia: Battle of La Haye-du-Puits).

Bradley finalizes the plan for Operation Cobra; St-Lô must first be secured to form the jump-off line. (Levine, 2007, 73).

Hedgerow fighting continues; First Army grinds toward Saint-Lô. U.S. units improvise “Culin rhino” hedgerow cutters. (U.S. Army Center of Military History; The D-Day Story, Portsmouth).

1944-07-11-Tuesday

82nd Airborne leaves for the UK and is replaced by the 8th Infantry Division; First Army opens its attack on Saint-Lô as part of the broader offensive. (Wikipedia: Battle of La Haye-du-Puits).

1944-07-12-Wednesday

Lt. Gen. Hodges reports the 8th Division stalled; Middleton relieves Maj. Gen. McMahon and appoints Brig. Gen. Donald A. Stroh; Germans are found to have withdrawn from Lastelle. (Wikipedia: Battle of La Haye-du-Puits).

U-boat Command recalls all non-snorkel submarines amid heavy losses. (Levine, 2007, 64).

1944-07-13-Thursday

British and Canadian soldiers enter the outskirts of Caen, but are stopped by surprisingly heavy improvised resistance from the Germans. (Bishop 2003).

1944-07-14-Friday

U.S. objectives reached: 90th Division reaches the Sèves River; 8th Division secures the ridge over the Ay; 79th Division reaches the Ay River—concluding the battle’s advance. (Wikipedia: Battle of La Haye-du-Puits).

1944-07-15-Saturday

Hill 122 north of St-Lô falls after hard fighting. (Levine, 2007, 73).

1944-07-16-Sunday

1944-07-17-Monday

The isolated U.S. battalion northeast of St-Lô is saved; Task Force C will later enter the city. (Levine, 2007, 73).

1944-07-18-Tuesday

Evening — St-Lô entered; German retreat begins. (Levine, 2007, 74).

Saint-Lô falls after heavy fighting. (U.S. Army Center of Military History; The D-Day Story, Portsmouth).

U.S. forces gradually bring the much-contested town of Saint-Lô under their control. Saint-Lô provides a jumping-off point for assaults out of the southern sector of the Cotentin peninsula. (Bishop 2003).

Operation Goodwood

The British 2nd Army launches Operation Goodwood. British armored units strike around the north of Caen and attempt to meet up with the 2nd Canadian Division moving around the south. Goodwood captures Caen but only advances 8 km (5 miles) toward Falaise before being halted on July 20. (Bishop 2003).

1944-07-19-Wednesday

1944-07-20-Thursday

Failed coup in Germany; Levine marks this as a hinge (war drags on nine more months). (Levine, 2007, 72).

1944-07-21-Friday

1944-07-22-Saturday

1944-07-23-Sunday

1944-07-24-Monday

Cobra scrubbed by weather; some bombers drop anyway, causing friendly losses. (Levine, 2007, 75).

Pre-assault bombardment for Operation Cobra begins west of Saint-Lô; weather and short-drops cause severe friendly-fire incidents, delaying the main attack. (U.S. Army Center of Military History).

U.S. forces in the Cotentin peninsula launch Operation Cobra, aiming to break through German lines and clear the Allied path through to Avranches. (Bishop 2003).

Northern France Breakout Across Normandy

25 July to Late August 1944

1944-07-25-Tuesday

Operation Cobra begins. First U.S. Army ruptures German lines near Saint-Lô, opening the breakout. (National WWII Museum).

Cobra’s main bombardment and ground attack; very heavy airstrike, with U.S. casualties from short drops. (Levine, 2007, 75).

1944-07-26-Wednesday

Cobra gains momentum; U.S. armored divisions push toward Coutances. (National WWII Museum).

Effects of the bombing crack the front; 2nd Armored cuts south of Coutances. (Levine, 2007, 75).

1944-07-27-Thursday

1944-07-28-Friday

Cobra continues; U.S. forces surge south through the bocage. (National WWII Museum).

U.S. advance surges; Bradley gives Patton supervision of VIII Corps. The Avranches—Pontaubault corridor is the gateway south. (Levine, 2007, 75).

1944-07-29-Saturday

1944-07-30-Sunday

Avranches corridor secured; gateway to Brittany opens. (U.S. Army Center of Military History).

The 1st U.S. Army takes Avranches and holds it against counterattack from the German 7th Army. (Bishop 2003).

1944-07-31-Monday

By this date, Third Army is about to become operational (Aug 1). (Levine, 2007, 75).

August 1944

Mortain counterattack, closing the Falaise pocket, Paris and the Seine

1944-08-01-Tuesday

Hitler notes the Avranches “bottleneck” opportunity; orders a counter-offensive. (Levine, 2007, 79).

Third U.S. Army activates and joins the pursuit while First Army drives east. (U.S. Army Center of Military History).

U.S. 3rd Army under General George S. Patton attacks through the Avranches gap and drives for the Loire and into Brittany. (Bishop 2003).

1944-08-02-Wednesday

1944-08-03-Thursday

1944-08-04-Friday

German XXX Corps in Brittany, unable to hold Patton’s advance, withdraws into the coastal ports and turns them into siege positions. (Bishop 2003).

1944-08-05-Saturday

1944-08-06-Sunday

1944-08-07-Monday

Mortain counterattack (Operation Lüttich – Unternehmen Lüttich) begins. German XLVII Panzerkorps strikes toward Avranches to cut U.S. lines. (Ibiblio).

After midnight — Mortain begins; 30th Infantry Division bears the brunt; Hill 317 holds out. (Levine, 2007, 79–80).

German counterattack toward Avranches captures Mortain and drives about 11 km (7 miles) before being halted by Allied artillery and airstrikes. (Bishop 2003).

The 1st Canadian Army commits to a major offensive south of Caen, advancing several miles toward Falaise. (Bishop 2003).

1944-08-08-Tuesday

First phase of Operation Totalize launched by II Canadian Corps using mechanized infantry; tanks and Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers advance behind a rolling barrage. British and Canadian forces capture Verrières Ridge by noon despite fog and strong German resistance. (Wikipedia: Operation Totalize).

Allied “Totalize” night assault toward Falaise opens. (Levine, 2007, 81–82).

General Omar Bradley, commander of the 12th U.S. Army, proposes to Montgomery a plan to trap 21 German divisions in the Falaise–Argentan pocket. Plan accepted. (Bishop 2003).

1944-08-09-Wednesday

German armoured counter-attack by the 12th SS Panzer Division fails but slows Allied armored formations, especially east of the Caen-Falaise road; west of the road German infantry at Cintheaux hold up advances. (Wikipedia: Operation Totalize).

Canadian armor suffers disaster (e.g., 28th British Columbia Regiment destroyed) during the push toward Falaise. (Levine, 2007, 81).

1944-08-10-Thursday

Allied forces capture Hill 195 (west of the main road, between Cintheaux and Falaise) in a night attack; Germans withdraw and prepare a defensive line on the Laison River. (Wikipedia: Operation Totalize).

Renewed Canadian attack (post-Totalize) goes badly and is stopped; plans reset. (Levine, 2007, 81).

Having reached Le Mans on August 8, Patton swings his 3rd Army north, reaching Argentan on August 13. (Bishop 2003).

1944-08-11-Friday

1944-08-12-Saturday

Hill 314 near Mortain still holds; Allied airpower devastates German forces. (Ibiblio).

Hill 317, Mortain, finally relieved after six days. (Levine, 2007, 80).

Falaise pocket begins to form as Allied pincers close on German 7th Army and Panzergruppe West. (U.S. Army Center of Military History).

1944-08-13-Sunday

German Mortain counterattack collapses. (Ibiblio).

French patrol enters (then is forced out of) Argentan; the short-envelopment drive tightens. (Levine, 2007, 81).

1944-08-14-Monday

Operation TRACTABLE opens toward Falaise; some friendly-fire losses from short bombing. (Levine, 2007, 81).

Large sections of Patton’s U.S. 3rd Army break away from Falaise and begin the drive east toward Chartres and Paris. (Bishop 2003).

1944-08-15-Tuesday

Von Kluge “disappears” under air attack; Southern France landings also occur this day in Levine’s narrative frame. (Levine, 2007, 81, 85–87).

1944-08-16-Wednesday

Montgomery orders the final pinch at Trun/Chambois. (Levine, 2007, 81–82).

The Canadians reach Falaise after a week of fighting. German forces are finally permitted to withdraw. Patton’s 3rd Army reaches Chartres. (Bishop 2003).

1944-08-17-Thursday

1944-08-18-Friday

1944-08-19-Saturday

Crossings of the Seine (e.g., Mantes-Gassicourt) begin. (Wikipedia).

Paris uprising begins. (Levine, 2007, 84).

One division of the U.S. XV Corps crosses the Seine at Mantes Gassicourt. (Bishop 2003).

1944-08-20-Sunday

The Falaise pocket containment complete; German retreat chaotic.

By this date, the U-boat campaign has ground to a halt in the Channel. (Levine, 2007, 64).

The Falaise pocket is closed by U.S. and Canadian forces. Most of the German forces in Normandy are trapped in an area 9 by 11 km (5.5 by 6.8 miles). (Bishop 2003).

1944-08-21-Monday

The Falaise–Argentan pocket closed; German forces in Normandy shattered. (U.S. Army Center of Military History).

1944-08-22-Tuesday

The Falaise pocket sealed; 50,000 prisoners taken. (Levine, 2007, 82).

The surviving Germans in the Falaise pocket surrender. Up to 50,000 are taken prisoner and 10,000 killed. (Bishop 2003).

1944-08-23-Wednesday

1944-08-24-Thursday

1944-08-25-Friday

Liberation of Paris

Liberation of Paris by French 2e DB with U.S. 4th Infantry Division support. (Wikipedia). Paris is liberated by the Allies. Patton’s forces secure additional Seine crossings at Louviers and Elbeuf. (Bishop 2003).

Skies clear; Allied aircraft savage German Seine crossings; Paris is freed. (Levine, 2007, 84).

1944-08-26-Saturday

1944-08-27-Sunday

1944-08-28-Monday

1944-08-29-Tuesday

1944-08-30-Wednesday

1944-08-31-Thursday

German remnants stream east of the Seine, ending the Normandy phase of Overlord. (Wikipedia).

September 1944

Pursuit, Antwerp captured, Market-Garden

1944-09-01-Friday

1944-09-02-Saturday

1944-09-03-Sunday

Guards Armoured liberates Brussels. (Levine, 2007, 100).

1944-09-04-Monday

11th Armoured enters Antwerp, docks largely intact thanks to Belgian resistance. (Levine, 2007, 100).

1944-09-05-Tuesday

1944-09-06-Wednesday

1944-09-07-Thursday

1944-09-08-Friday

1944-09-09-Saturday

1944-09-10-Sunday

SHAEF/army-group conference as plans pivot to a Rhine bridgehead and Antwerp’s opening. (Levine, 2007, 125–126). Eisenhower approves Operation Market Garden, designed by Montgomery. Airborne deployment aims to capture key bridges at Eindhoven, Veghel, Grave, Nijmegen, and Arnhem, and hold them until British XXX Corps (advancing 150 km from the Meuse–Escaut canal) can relieve them. (Bishop 2003).

1944-09-11-Monday

U.S. forces link up with 6th Army Group—XV Corps meets French First Army. (Levine, 2007, 120).

1944-09-12-Tuesday

Le Havre surrenders after 10–12 Sept assault by British 49th and 51st Divisions. (Levine, 2007, 123).

1944-09-13-Wednesday

First Army becomes entangled in the Hürtgen Forest south of Aachen, starting a costly episode. (Levine, 2007, 132).

1944-09-14-Thursday

1944-09-15-Friday

1944-09-16-Saturday

1944-09-17-Sunday

Operation Market-Garden

Eindhoven–Nijmegen–Arnhem

Operation Market Garden begins (Levine, 2007, 109–110).

- British 1st Airborne Division, U.S. 82nd Airborne, and U.S. 101st Airborne drop over Eindhoven, Veghel, Grave, and Arnhem.

- Landings around Eindhoven and Veghel succeed.

- U.S. 82nd Airborne secures Grave bridge.

- U.S. 101st secures Eindhoven and Veghel bridges.

- British 1st Airborne secures Arnhem bridge approaches but faces heavy resistance. (Bishop 2003).

1944-09-18-Monday

British XXX Corps links with U.S. 101st Airborne at Eindhoven and Veghel.

Further progress up the main Eindhoven road is slowed under intense German resistance. (Bishop 2003).

1944-09-19-Tuesday

Stalled at Nijmegen. (Levine, 2007, 114).

British XXX Corps joins U.S. 82nd Airborne at Grave at 8:20 a.m. (Bishop 2003).

1944-09-20-Wednesday

Famous Waal boat assault (26 boats usable) in the afternoon; both Nijmegen bridges taken intact that evening. (Levine, 2007, 114).

U.S. 82nd Airborne, reinforced by XXX Corps, assaults Nijmegen bridges. After heavy fighting and river crossing, Nijmegen bridges are captured.

German counterattacks delay XXX Corps advance another 24 hours. (Bishop 2003).

1944-09-21-Thursday

Frost’s last defenders at Arnhem bridge compelled to surrender; 1st Airborne holds Oosterbeek perimeter. (Levine, 2007, 115).

German counterattacks press hard on British paratroopers at Arnhem.

U.S. airborne divisions fight desperately to hold their corridors.

Arnhem bridge perimeter is cut off. XXX Corps advances just north of Nijmegen. (Bishop 2003).

1944-09-22-Friday

Boulogne captured by 3rd Canadian Division. (Levine, 2007, 123).

Polish Parachute Brigade lands south of Arnhem in support of the British 1st Airborne. Fierce fighting continues, with Polish forces unable to relieve Arnhem bridge. (Bishop 2003).

1944-09-23-Saturday

Evacuation of German Fifteenth Army across the Scheldt completed (≈86,000 men). (Levine, 2007, 100).

1944-09-24-Sunday

Evacuation decision taken. (Levine, 2007, 116).

1944-09-25-Monday

Night withdrawal of 1st Airborne across the Rhine begins. (Levine, 2007, 116).

Survivors of British 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem retreat across the Neder Rijn after failing to hold.

XXX Corps halts short of Arnhem.

2,000 escape; 7,000 prisoners taken; 1,000 killed. (Bishop 2003).

1944-09-26-Tuesday

1944-09-27-Wednesday

Remaining British and Polish forces withdraw south of the Neder Rijn.

German forces retain Arnhem bridgehead and hold ground for two months. (Bishop 2003).

1944-09-28-Thursday

1944-09-29-Friday

In Lorraine, a major 11th Panzer attack (begun 25 Sept) is finally stopped. (Levine, 2007, 120).

1944-09-30-Saturday

—

October–November 1944

Aachen, the Scheldt, Operation Queen and opening Antwerp

1944-10-01-Sunday

1944-10-02-Monday

First Canadian Army’s Scheldt campaign begins to seal off South Beveland and clear the Breskens Pocket. (Levine, 2007, 126–127).

1944-10-03-Tuesday

1944-10-04-Wednesday

1944-10-05-Thursday

1944-10-06-Friday

1944-10-07-Saturday

1944-10-08-Sunday

1944-10-09-Monday

1944-10-10-Tuesday

1944-10-11-Wednesday

1944-10-12-Thursday

1944-10-13-Friday

1944-10-14-Saturday

1944-10-15-Sunday

1944-10-16-Monday

1944-10-17-Tuesday

1944-10-18-Wednesday

1944-10-19-Thursday

1944-10-20-Friday

1944-10-21-Saturday

Aachen falls after encirclement and brutal urban fighting (first major German city taken). (Levine, 2007, 133–134).

1944-10-22-Sunday

1944-10-23-Monday

1944-10-24-Tuesday

1944-10-25-Wednesday

1944-10-26-Thursday

1944-10-27-Friday

1944-10-28-Saturday

1944-10-29-Sunday

1944-10-30-Monday

1944-10-31-Tuesday

1944-11-01-Wednesday

Amphibious landings at Flushing and Westkapelle open the assault on Walcheren Island. (Levine, 2007, 129).

1944-11-02-Thursday

Continued fighting on Walcheren Island. (Levine, 2007, 129).

V Corps commits 28th Infantry Division to seize Schmidt; attack begins. (Levine, 2007, 135).

1944-11-03-Friday

Schmidt taken, then quickly lost to strong counterattacks; fighting along the Kall trail; Americans hold Kommerscheidt. (Levine, 2007, 135).

Fighting continues on Walcheren Island. (Levine, 2007, 129).

1944-11-04-Saturday

1944-11-05-Sunday

1944-11-06-Monday

Surrender at Middelburg ends organized resistance on Walcheren. (Levine, 2007, 129).

1944-11-07-Tuesday

1944-11-08-Wednesday

1944-11-09-Thursday

1944-11-10-Friday

1944-11-11-Saturday

1944-11-12-Sunday

1944-11-13-Monday

1944-11-14-Tuesday

1944-11-15-Wednesday

1944-11-16-Thursday

U.S. First & Ninth Armies launch “Operation Queen” toward the Roer; biggest direct-support bomber effort of the war. (Levine, 2007, 137–138).

1944-11-17-Friday

1944-11-18-Saturday

1944-11-19-Sunday

1944-11-20-Monday

In Operation Queen, U.S. armor fights the largest tank battle yet for the Americans on the Roer front. (Levine, 2007, 141).

1944-11-21-Tuesday

1944-11-22-Wednesday

1944-11-23-Thursday

1944-11-24-Friday

1944-11-25-Saturday

1944-11-26-Sunday

First small coasters enter Antwerp. (Levine, 2007, 130).

1944-11-27-Monday

1944-11-28-Tuesday

1944-11-29-Wednesday

Ocean-going ships reach Antwerp: the Scheldt is open. (Levine, 2007, 130).

1944-11-30-Thursday

December 1944

The Ardennes (“Battle of the Bulge”) and German Alsace offensive

1944-12-01-Friday

Ninth Army reaches the Roer and halts pending the dams situation. (Levine, 2007, 141).

1944-12-02-Saturday

1944-12-03-Sunday

U.S. 95th Division seizes a bridge at Saarlautern over the Saar. (Levine, 2007, 141).

1944-12-04-Monday

1944-12-05-Tuesday

1944-12-06-Wednesday

1944-12-07-Thursday

1944-12-08-Friday

1944-12-09-Saturday

1944-12-10-Sunday

1944-12-11-Monday

1944-12-12-Tuesday

1944-12-13-Wednesday

First Army renews the push for the Roer dams (2nd, 78th, and elements of 99th Infantry Divisions). (Levine, 2007, 139).

1944-12-14-Thursday

1944-12-15-Friday

1944-12-16-Saturday

German offensive opens in the Ardennes; initial breakthroughs, Schnee-Eifel surrenders, and the battle for St-Vith begin. (Levine, 2007, 151–153, 160–163).

1944-12-17-Sunday

Ardennes fighting continues; German advance develops. (Levine, 2007, 151–153, 160–163).

1944-12-18-Monday

U.S. armor teams block roads into Bastogne; 2nd Panzer is delayed; Panzer Lehr held up. (Levine, 2007, 162).

1944-12-19-Tuesday

U.S. armor continues to block German thrusts; Bastogne remains threatened. (Levine, 2007, 162).

1944-12-20-Wednesday

Bastogne encircled as supply line is cut. (Levine, 2007, 162–163).

1944-12-21-Thursday

1944-12-22-Friday

McAuliffe’s famous “Nuts!” reply to German surrender demand. (Levine, 2007, 162–163).

1944-12-23-Saturday

Skies clear; Allied air power and airdrops resume over Bastogne. (Levine, 2007, 162–163).

1944-12-24-Sunday

VII Corps breaks the German dash to the Meuse. (Levine, 2007, 160–164).

1944-12-25-Monday

Christmas Day — 2nd Armored Division smashes 2nd Panzer. (Levine, 2007, 160–164).

1944-12-26-Tuesday

4th Armored Division opens the corridor into Bastogne and lifts the siege. (Levine, 2007, 160–164).

1944-12-27-Wednesday

1944-12-28-Thursday

1944-12-29-Friday

1944-12-30-Saturday

Renewed German effort against the Bastogne salient. (Levine, 2007, 164).

1944-12-31-Sunday

German counterattacks around Bastogne continue. (Levine, 2007, 164).

—

January 1945

The Ardennes and the Eastern Front

1945-01-01-Monday

Luftwaffe launches Operation Bodenplatte, a massive low-level New Year’s Day strike; ~300 Allied planes lost but the Luftwaffe is destroyed as an effective force in the West. (Levine, 2007, 164).

1945-01-02-Tuesday

1945-01-03-Wednesday

First Army authorized to attack on the northern face of the Bulge. (Levine, 2007, 171).

1945-01-04-Thursday

1945-01-05-Friday

Bastogne counterattacks peter out; Bulge erosion continues. (Levine, 2007, 164).

1945-01-06-Saturday

1945-01-07-Sunday

1945-01-08-Monday

1945-01-09-Tuesday

1945-01-10-Wednesday

1945-01-11-Thursday

1945-01-12-Friday

1945-01-13-Saturday

1945-01-14-Sunday

1945-01-15-Monday

Levine notes the Soviet Vistula offensive begins in mid-January, diverting German reserves westward. (Levine, 2007, 171–172).

1945-01-16-Tuesday

1945-01-17-Wednesday

1945-01-18-Thursday

1945-01-19-Friday

1945-01-20-Saturday

Levine marks the continued Soviet drive west in late January, setting the stage for the final Allied push. (Levine, 2007, 171–172).

1945-01-21-Sunday

1945-01-22-Monday

1945-01-23-Tuesday

1945-01-24-Wednesday

Night 24–25 Jan German assault in Alsace (Nordwind phase) is repulsed. (Levine, 2007, 171).

1945-01-25-Thursday

1945-01-26-Friday

1945-01-27-Saturday

1945-01-28-Sunday

1945-01-29-Monday

Army Group G absorbs Army Group Oberrhein; crisis in Alsace ends with German retreat. (Levine, 2007, 171).

1945-01-30-Tuesday

1945-01-31-Wednesday

February 1945

Colmar, the Roer Dams, Operation Grenade

1945-02-01-Thursday

1945-02-02-Friday

1945-02-03-Saturday

Colmar Pocket eliminated; survivors escape over the Rhine. (Levine, 2007, 175).

1945-02-04-Sunday

1945-02-05-Monday

U.S. 78th Division and CCB/7th Armored strike the Schwammenauel dam; 9th Division takes Urft dam. (Levine, 2007, 175).

1945-02-06-Tuesday

1945-02-07-Wednesday

1945-02-08-Thursday

1945-02-09-Friday

By late evening, Schwammenauel valves destroyed; controlled release floods the Roer. (Levine, 2007, 175).

1945-02-10-Saturday

Planned Roer crossing (Ninth Army) for Feb 10 is postponed by the flood. (Levine, 2007, 175).

1945-02-11-Sunday

1945-02-12-Monday

German XLVII Panzer Corps counterattacks the British in the Reichswald sector. (Levine, 2007, 176).

1945-02-13-Tuesday

1945-02-14-Wednesday

1945-02-15-Thursday

1945-02-16-Friday

1945-02-17-Saturday

1945-02-18-Sunday

1945-02-19-Monday

1945-02-20-Tuesday

1945-02-21-Wednesday

1945-02-22-Thursday

1945-02-23-Friday

Operation GRENADE—Ninth Army crosses the Roer; VII Corps also attacks. (Levine, 2007, 177).

1945-02-24-Saturday

1945-02-25-Sunday

1945-02-26-Monday

1945-02-27-Tuesday

1945-02-28-Wednesday

March 1945

The Rhine crossed: Cologne, Remagen, Oppenheim; Ruhr encirclement begins

1945-03-01-Thursday

1945-03-02-Friday

1945-03-03-Saturday

Ninth Army links with First Canadian Army, sealing off the Rhineland. (Levine, 2007, 177).

1945-03-04-Sunday

1945-03-05-Monday

Ninth Army proposes a Rhine assault near Düsseldorf. (Levine, 2007, 178).

1945-03-06-Tuesday

Cologne taken by Allied forces. (Levine, 2007, 178).

1945-03-07-Wednesday

Cologne fully secured; First Army reaches the Rhine. (Levine, 2007, 178).

Remagen bridge seized by 9th Armored Division; A/27th Armored Infantry crosses under fire. (Levine, 2007, 179–180).

1945-03-08-Thursday

1945-03-09-Friday

Ferry crossings at Remagen begin. (Levine, 2007, 179–180).

1945-03-10-Saturday

Engineers begin bridging operations at Remagen. (Levine, 2007, 179–180).

Wesel bridges destroyed by the Germans; preparations for Plunder/Varsity. (Levine, 2007, 177).

1945-03-11-Sunday

1945-03-12-Monday

1945-03-13-Tuesday

1945-03-14-Wednesday

1945-03-15-Thursday

1945-03-16-Friday

1945-03-17-Saturday

Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen collapses under stress and attack. (Levine, 2007, 180).

1945-03-18-Sunday

1945-03-19-Monday

Patton’s XII Corps stages feints near Mainz. (Levine, 2007, 184–185).

1945-03-20-Tuesday

1945-03-21-Wednesday

1945-03-22-Thursday

1945-03-23-Friday

That night the 5th Division crosses at Oppenheim/Nierstein, expanding a southern bridgehead. (Levine, 2007, 184–185).

1945-03-24-Saturday

Operation VARSITY—British 6th Airborne and U.S. 17th Airborne drop east of the Rhine near Wesel. (Levine, 2007, 183).

1945-03-25-Sunday

First Army breaks out from the Remagen bridgehead; the German defense unravels. (Levine, 2007, 183).

1945-03-26-Monday

1945-03-27-Tuesday

1945-03-28-Wednesday

First and Third Armies link up near the Limburg–Wiesbaden autobahn, closing a huge pocket west of the Rhine. (Levine, 2007, 187).

1945-03-29-Thursday

1945-03-30-Friday

1945-03-31-Saturday

April 1945

To the Elbe, the Ruhr pocket, and the Baltic; Berlin surrounded

1945-04-01-Sunday

At Lippstadt, 3rd Armored links with 2nd Armored—Ruhr pocket sealed. (Levine, 2007, 190).

1945-04-02-Monday

1945-04-03-Tuesday

1945-04-04-Wednesday

Ohrdruf concentration camp liberated, the first such camp reached by U.S. forces in Levine’s narrative. (Levine, 2007, 193).

1945-04-05-Thursday

1945-04-06-Friday

1945-04-07-Saturday

1945-04-08-Sunday

1945-04-09-Monday

1945-04-10-Tuesday

1945-04-11-Wednesday

Nordhausen camp liberated by U.S. forces. (Levine, 2007, 193).

1945-04-12-Thursday

Buchenwald camp liberated. (Levine, 2007, 193).

1945-04-13-Friday

1945-04-14-Saturday

Allied Elbe bridgeheads probed and partly abandoned under heavy German fire. (Levine, 2007, 193).

1945-04-15-Sunday

1945-04-16-Monday

Soviets begin their final offensive on the Oder. (Levine, 2007, 198).

1945-04-17-Tuesday

Magdeburg falls after air attack and fighting. (Levine, 2007, 193).

1945-04-18-Wednesday

Most defenders in the Ruhr pocket give up; organized resistance collapses over 16–18 April. (Levine, 2007, 192).

1945-04-19-Thursday

1945-04-20-Friday

Leipzig surrenders. (Levine, 2007, 193).

1945-04-21-Saturday

1945-04-22-Sunday

1945-04-23-Monday

1945-04-24-Tuesday

1945-04-25-Wednesday

U.S.–Soviet linkup at Torgau on the Elbe; Germany cut in two. (Levine, 2007, 193).

1945-04-26-Thursday

1945-04-27-Friday

1945-04-28-Saturday

1945-04-29-Sunday

British and U.S. forces cross the Elbe (Second Army & XVIII Airborne Corps). (Levine, 2007, 200–201).

1945-04-30-Monday

Hitler commits suicide in Berlin. (Levine, 2007, 200–201).

May 1945

Surrender

1945-05-01-Tuesday

Karl Dönitz offers to surrender to the Western powers only, seeking to keep fighting in the East. (Levine, 2007, 202).

1945-05-02-Wednesday

Berlin surrenders. (Levine, 2007, 198).

1945-05-03-Thursday

Doenitz authorizes partial capitulations. (Levine, 2007, 202).

1945-05-04-Friday

Surrender of northwest Germany signed, effective May 5. (Levine, 2007, 202).

1945-05-05-Saturday

Army Group G and Nineteenth Army surrender. (Levine, 2007, 202).

1945-05-06-Sunday

1945-05-07-Monday

Jodl signs unconditional surrender at Reims, to take effect two days later. (Levine, 2007, 202).

1945-05-08-Tuesday

V-E Day — fighting mostly ceased even before the formal surrender took effect, with some exceptions. (Levine, 2007, 202–203).

1945-05-09-Wednesday

1945-05-10-Thursday

1945-05-11-Friday

1945-05-12-Saturday

1945-05-13-Sunday

1945-05-14-Monday

1945-05-15-Tuesday

1945-05-16-Wednesday

1945-05-17-Thursday

1945-05-18-Friday

1945-05-19-Saturday

1945-05-20-Sunday

1945-05-21-Monday

1945-05-22-Tuesday

1945-05-23-Wednesday

1945-05-24-Thursday

1945-05-25-Friday

1945-05-26-Saturday

1945-05-27-Sunday

1945-05-28-Monday

1945-05-29-Tuesday

1945-05-30-Wednesday

1945-05-31-Thursday

Phase markers Levine explicitly names

- “The Normandy Beachhead” (Chapter 2 framing of June–July 1944). (Levine, 2007, 51ff).

- “The Liberation of Western Europe” (Chapter 3 framing of the August–September pursuit and the Riviera landing). (Levine, 2007, 77ff).

- “The Fall Fighting on the German Frontier” (Chapter 4 framing of October–November fighting at Aachen, the Roer/Queen, and the Scheldt). (Levine, 2007, 103ff).

- “The German Counteroffensives in the Ardennes and Alsace” (Chapter 5: December 1944–January 1945). (Levine, 2007, 145ff).

- “The March to Victory, January–May 1945” (Chapter 6 framing of Remagen, Rhine crossings, Ruhr, Elbe, Berlin, and surrender). (Levine, 2007, 169ff).

Levine, Alan J. D-Day to Berlin…

Bibliography

Bishop, Chris. Campaigns of World War II Day by Day. Singapore: Amber Books, 2003.

Hart, Stephen. The D-Day Landings: Northern France, 6 June 1944. London: COI Communications, 2004

Levine, Alan J. D-Day to Berlin: The Northwest Europe Campaign, 1944–45. First edition. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2007.

Williams, Mary H., comp., Chronology, 1941–1945, United States Army in World War II: Special Studies, Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, Washington, DC, 1960.