On December 16, 1944, before dawn, the Ardennes Offensive—Germany’s last major counteroffensive on the Western Front—began.

At the forefront of this attack was Kampfgruppe Peiper of the 1. SS-Panzer-Division “Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler”, commanded by SS-Obersturmbannführer Joachim Peiper.

The unit’s mission was to exploit gaps in the American defenses and advance rapidly toward the Maas (Meuse) river, seizing vital bridges to pave the way for a larger German breakthrough.

Saturday, December 16, 1944

As the offensive commenced, Kampfgruppe Peiper moved out from Blankenheim, Germany, beginning its advance westward into Belgium.

Early Morning

Preparation and First Movements. Kampfgruppe Peiper assembles and prepares to advance.

Blankenheim, Germany

As the lead element of the German offensive in the Ardennes, Kampfgruppe Peiper’s aim was to push westward toward the Meuse River, exploiting gaps in American lines created by the infantry divisions ahead of them.

In the early hours of December 16, 1944, Kampfgruppe Peiper assembled east of Stadtkyll, Germany (in an area possibly near Dahlem?), preparing to spearhead the 6. Panzer-Armee’s offensive. The plan relied on the 3. Fallschirmjäger-Division and the 12. Volksgrenadier-Division breaking through American defenses at Losheimergraben and Buchholz, clearing the way for Peiper’s mechanized forces. The group moved through Dahlem, Stadtkyll, Kronenburg, Hallschlag, Scheid, and Losheim.

Kampfgruppe Peiper’s route on December 16, 1944

Kampfgruppe Peiper followed a path through Dahlem, Stadtkyll, Kronenburg, Hallschlag, Scheid and Losheim.

05:30 – A massive artillery bombardment erupted across a 120 km front, from Monjoie to Echternach. This was the signal for the German Ardennes Offensive to begin..

The first wave of German infantry broke through American front-line positions, surprising and overwhelming defenders. Cities like Verviers, Eupen, and Malmedy were shelled by heavy rail-mounted artillery, causing civilian casualties. From La Gleize, local inhabitants could hear the artillery barrage against Malmedy.

Morning

Kampfgruppe Peiper Awaits Clearance: The plan was for the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division and the 12th Volksgrenadier Division to break through the American defenses at Losheimergraben and Buchholz, clearing the way for Peiper’s tanks.

Losheim

07:00 – The 12. Volksgrenadier-Division moves to clear Losheim, repair roads and bridges, and secure a path for Kampfgruppe Peiper. The division attacks Losheimergraben but encounters stiff American resistance.

07:30 – The 12. Volksgrenadier-Division fails to take Losheimergraben, delaying Kampfgruppe Peiper’s advance.

Battle of Lanzerath Ridge

The Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 9, 3. Fallschirmjäger-Division, is ordered to lead the attack through Lanzerath, clear the village, and advance toward Honsfeld and Büllingen. As they advance south of Losheimergraben toward Lanzerath, they engage Lieutenant Bouck’s 18-man reconnaissance platoon (99th Infantry Division). The American unit holds its position for nearly an entire day, delaying the German advance. (The Battle of Lanzerath Ridge page)

12. Volksgrenadier-Division and 3. Fallschirmjäger-Division (Battle of Lanzerath Ridge)

Afternoon

14:00 – SS-Obersturmbannführer Joachim Peiper receives orders to begin advancing. He inspects the front, finding roads clogged with horse-drawn artillery and immobilized German vehicles. His troops were forced to push through horse-drawn artillery columns of the 18th Volksgrenadier Division, causing chaos.

Kampfgruppe Peiper is delayed due to congestion along the Blankenheim-Schnied road and unexpected resistance at Losheimergraben. Paratroopers assigned to clear the way remain held up by Lt. Bouck’s platoon at Lanzerath Ridge, further stalling the advance.

Scheid Railway Bridge

Location: One kilometer west of Scheid, Germany | GPS Coordinates: 50°21’10.2″N 6°23’49.7″E

14:15 – The Scheid railway bridge, spanning the Malmedy-Stadtkyll railway line, had been blown up by retreating German forces in September 1944. By December 16, it remained unrepaired, as the engineering battalion of the 12. Volksgrenadier-Division lacked the resources for reconstruction. Arriving at the bridge at approximately 14:15, Kampfgruppe Peiper encountered a bottleneck, with German troops queuing at the destroyed bridge. Peiper, frustrated by the delay, ordered his column to force its way forward, pushing obstacles aside1. Instead of waiting for engineers, he decided to circumvent the bridge by moving 50 meters north, descending a track to the right, crossing the railway, and rejoining the main road (Gillet, 2003). Engineers begin constructing a temporary bridge, expected to be usable by light vehicles within hours2.

17:00 – Peiper receives new orders: Instead of following the original route through Losheimergraben, he is rerouted through Lanzerath, where the Fallschirm-Jäger-Regiment 9 (3. Fallschirmjäger-Division) is still engaged with Bouck’s platoon.

Evening

Losheim

19:30 – Kampfgruppe Peiper arrives at Losheim, bypassing the destroyed Scheid Railway Bridge, but encounters another demolished overpass at Losheimergraben (?).

As Kampfgruppe Peiper advances northwest of Merlscheid, within 500 meters of Lanzerath, SS-Obersturmführer Werner Sternebeck’s Panzer IVH strikes a mine. The explosion buckles the tank, rendering one track inoperable. While repair is possible, the advance cannot be delayed. Sternebeck, leading the Spitze (spearhead) of the column, transfers to Panzer IV #612, commanded by SS-Untersturmführer Karl-Heinz Asmussen. Frustrated by losses, Sternebeck acknowledges that the two Panther tanks, intended as breakthrough vehicles, were disabled without encountering enemy fire. Despite the setback, Sternebeck presses forward, aware that Peiper will not tolerate delays 3.

Lanzerath

A minefield slows the advance in Lanzerath

Just outside Lanzerath, Peiper’s lead Panther tank strikes a mine, confirming that the road has not been properly cleared. Engineers from SS-Pionier-Bataillon 1 begin removing mines in the dark, further delaying the advance. Several more tanks hit mines, including one commanded by Leutnant Werner Sternebeck.

00:00 – Kampfgruppe Peiper reaches Lanzerath, having navigated the narrow, darkened roads leading to the hilltop village. By radio communication, I. SS-Panzerkorps informs Peiper that Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 9 has broken through the initial American defensive line but has been repulsed three times while attempting to advance beyond Lanzerath toward Honsfeld. Unbeknownst to Peiper, the resistance his corps reported was almost certainly due to the defense mounted by Lieutenant Lyle Bouck’s I&R platoon, which had successfully held off the Fallschirmjäger attacks 4.

Peiper has a heated argument with Oberst Hellmut Hoffmann, commander of Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 9

As Kampfgruppe Peiper arrives in Lanzerath, Peiper enters Café Scholzen, which has been converted into a temporary headquarters for the Fallschirmjäger. Inside, German paratroopers and captured American soldiers are present. Among the prisoners from the I&R Platoon, 394th Infantry Regiment, is Lieutenant Lyle Bouck, holding Pvt. William J. Tsakanikis, who is severely wounded. Some prisoners are wounded or unconscious, while others remain under guard 5.

Kampfgruppe Peiper establishes a command post in a café in Lanzerath, where SS-Obersturmbannführer Joachim Peiper has a heated argument with Oberst Hellmut Hoffmann, commander of Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 9 (from 9 October 1944 to 1 March 1945)6.

Hoffmann reports that American resistance in Lanzerath was stronger than expected and that his men require rest before resuming the attack in the morning. Peiper, frustrated by the delays in clearing the route, confronts Hoffmann over the failure to secure the way forward.

Sunday, December 17, 1944

Early Morning.

On the morning of December 17, 1944, Kampfgruppe Peiper advanced westward from Lanzerath, toward Buchholz, capturing Honsfeld at dawn and encountering only scattered American resistance.

At 03:00, Kampfgruppe Peiper resumes its advance, frustrated by delays. Peiper orders his Panzers and Panzergrenadiers to move forward, accompanied by a battalion of paratroopers from the 3. Fallschirmjäger-Division, which he has attached to his force. Assessing that the Volksgrenadiers are unable to secure the breakthrough, Peiper takes direct control of the push toward the Meuse 7.

As Kampfgruppe Peiper advances toward Honsfeld, the lead elements—two Panther tanks and three armored half-tracks carrying SS-Panzergrenadiers—emerge from the woods where their road merges with another route. This road is crowded with American vehicles retreating toward Honsfeld, including elements of the 18th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, which had previously patrolled the Losheim Gap to maintain contact between the 99th and 106th Infantry Divisions. Rather than immediately opening fire, the German column blends into the retreating American vehicles, taking advantage of the darkness, fog, and confusion to conceal their presence 8.

04:00 – Peiper’s lead elements reach Buchholz, a cluster of buildings known as “Buchholz Farm” and a nearby railroad station. which American troops called “Buchholz Station” (actually Losheimergrahen Station).

Buchholz

05:00 – Kampfgruppe Peiper secures Buchholz, capturing American supply depots. 80 American soldiers surrender without resistance.

The column departs from Buchholz Farm and Lanzerath, where it had halted overnight, advancing down the narrow forest road toward Honsfeld. Minimal resistance is encountered, aside from two platoons of Company K, 3rd Battalion, 394th Infantry Regiment near Buchholz Farm, but they are quickly overrun 9.

After securing Buchholz, Kampfgruppe Peiper advances toward Honsfeld, a key American rest and supply area.

Honsfeld, Belgium

Time: 0500 hours, 17 December 1944

05:00 – As the vanguard of Kampfgruppe Peiper approaches a stream crossing before entering Honsfeld, they pass a lone U.S. armored car stopped on the side of the road. The vehicle belongs to A Troop, 32nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron and is commanded by Sergeant George Creel. His unit had moved to Honsfeld the previous night to avoid the advancing German forces through the Losheim Gap.

Creel and his crew had been assigned by First Lieutenant Robert B. Reppa to outpost the road from Lanzerath, tasked with warning of any German movement. Throughout the night of December 16-17, they observe only retreating American vehicles, some moving alone, others in groups, heading toward Honsfeld to escape the German advance. At 05:00, Creel and his men spot German Panther tanks and half-tracks filled with infantry passing by, led through the fog by a soldier carrying a flashlight. Surprised, Creel prepares to fire the armored car’s cannon, but the trailer attached to his vehicle blocks his shot. With Peiper’s column stretched out both ahead and behind, Creel and his crew recognize the futility of resistance. They abandon their vehicle and attempt to reach Honsfeld on foot to warn Lt. Reppa, but the effort is ultimately unsuccessful 10.

The image supposedly depicts Kampfgruppe Peiper’s troops; the logic would suggest they are moving west, the expected direction of their advance. However, from what I can gather, the Sd.Kfz. 251/1 featured in the photo is actually entering Honsfeld from the west and moving eastward.

The exact time at which Peiper’s column entered Honsfeld varies by source. Some indicate that by 05:00, his troops had reached the town, catching hundreds of exhausted American soldiers off guard as they slept, while others suggest that Honsfeld was already overrun by 04:00, with large amounts of American vehicles, fuel, and supplies falling into German hands.

Elements of the 394th Infantry Regiment (99th Infantry Division), alerted by battle sounds from the east and survivors from the 14th Cavalry Group retreating from Losheim, attempt to organize a defensive force.

A makeshift company is formed using available personnel and isolated soldiers, supported by anti-tank guns, and positioned south of Honsfeld. A half-track reconnaissance patrol is dispatched toward Lanzerath to detect approaching German forces. As Kampfgruppe Peiper arrives, the American defenders resist but are quickly overwhelmed. Some manage to retreat, while others surrender. Waffen-SS and Fallschirmjäger troops rapidly secure the village, clearing American soldiers still resisting from inside buildings11.

Kampfgruppe Peiper pushed through Honsfeld in the early morning, capturing and executing American prisoners in multiple incidents.

The exact events in Honsfeld remain unclear, but summary executions of U.S. prisoners took place. Reports suggest these were isolated acts carried out by Waffen-SS soldiers, either acting independently or following orders from officers enforcing directives not to take prisoners. Surviving prisoners are sent to Lanzerath, where some are executed after interrogation, while the majority are treated according to regulations12.

Notably, the crossroads shown above is also where the infamous photograph of German soldiers trying on boots and clothing taken from executed American soldiers was captured.

In addition to the massacres committed against U.S. forces, atrocities were carried out against civilians in Honsfeld.

A few nights after the German advance through Honsfeld, five SS soldiers called down into André Schroeder’s cellar, requesting a guide to the Jost farm. The civilians in the cellar hesitated, pressing closer together. Schroeder volunteered to lead them, but the SS soldiers had already noticed 16-year-old Erna Collas. They insisted that she accompany them instead 13.

Collas never returned. In May 1945, her body was discovered in a foxhole near the road to Büllingen. She had been shot seven times in the back. Due to the state of decomposition, it was impossible to determine whether she had suffered additional abuse before her death 14.

Waffen-SS troops searched houses where civilians had taken refuge in cellars. Among those found was 16-year-old Erna Collas . The soldiers claimed to be looking for someone to guide them to Büllingen and took her with them. Her body was later discovered along the road to Büllingen, hastily buried under a thin layer of soil. She had been shot three times in the back with a pistol. Along with Erna, two other civilians were killed in Honsfeld by German troops15.

Morning

Büllingen.

After consolidating the column, Peiper resumed his advance westward toward the Meuse. Aware that muddy roads would slow the movement of heavy vehicles, he diverted his Kampfgruppe toward Büllingen, planning to use the route originally assigned to the 12. SS-Panzer-Division, which was still delayed at Losheimergraben and Krinkelt.

Peiper’s forces capture a large American fuel depot in Büllingen

09:00 – In Büllingen, Peiper’s forces captured a large fuel depot containing 50,000 gallons of gasoline16, a critical resource after the previous day’s delays and detours. Along with 26,000 rations of food and other supplies seized by the Waffen-SS, the depot could have significantly aided their advance. However, eager to maintain momentum, Peiper left much of the fuel behind as his column, with Fallschirmjäger troops riding on the tanks, pressed westward.

09:30 – American artillery and aircraft attack Peiper’s column, inflicting minor losses.

11:00 – Büllingen is fully secured, and Peiper’s men refuel their tanks. During the occupation, American prisoners are executed, and several P-47 reconnaissance planes are destroyed on the ground.

Despite orders to wait for the rest of the 1. SS-Panzer-Division, Peiper disregards the command and moves southwest toward Baugnez crossroads. The column passes through Moderscheid, Schoppen, Ondenval, and Thirimont, encountering minimal resistance.

Möderscheid

10:00 – Peiper’s group left Büllingen and moved southwest towards Möderscheid.

It was more than likely between Möderscheid and Schoppen, perhaps even in Schoppen itself, that nine soldiers and two officers of the U.S. 3rd Armored Division were captured. These eleven men had been sent on patrol by Colonel Leander L. Doan, commanding officer of the 32nd Armored Regiment, part of Brigadier General Doyle O. Hickey’s Combat Command A17.

Walter J. Wendt, one of the survivors of this patrol, recounts:

“I remember that the reconnaissance company was stationed in the village of Breinig, near Stolberg. On the morning of 17 December 1944, we received orders to line up our jeeps. I thought it was just a routine patrol. But that morning, there were only eleven of us. We left the Stolberg area shortly after sunrise, with my jeep at the rear of the column. We drove until noon when suddenly, at a crossroads, we came face to face with a column of German tanks. Armed only with light weapons, we had no chance and surrendered. The Germans ordered us to place our jeeps within their column. I remember that mine was positioned approximately behind the tenth tank. While all of this was happening, a command car carrying officers pulled up next to us. One officer, in perfect English, asked if any of us spoke German. No one responded. Then, the column started moving again.” Henry Zach continues: “When they started going off-road through mud or rough terrain, it became too much for our jeep, and its transmission failed. Lieutenant Thomas McDermott and I were placed on the lead tank and travelled on it until we reached another group of German armoured vehicles near a café at a crossroads (Baugnez), where multiple roads branched off. This armoured column had captured an entire group of Americans*. When we arrived near the café, we were placed in a field south of the building18.”

(*)This group of American soldiers belonged to Battery B of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion. Its commanding officer was Captain Léon T. Scarborough.

Schoppen

10:30 – Kampfgruppe Peiper advances toward Schoppen, having encountered no further resistance after American armored artillery intervened near Büllingen.

Saint-Hubert Chapel

Before Faymonville, at Saint-Hubert Chapel, the tanks turn left onto a dirt road leading to Ondenval, then climb toward Thirimont, passing through the village for two and a half hours19.

12:15 –The 10. Kompanie, SS-Panzergrenadier-Regiment 2, led by Hauptsturmführer Georg Preuss, advances from Thirimont toward Ligneuville.

Seeking a shorter route to Ligneuville, Kampfgruppe Peiper attempts to bypass Bagatelle and Baugnez crossroads by taking a rural track leading to N23 through the Hauts Sarts wooded area.

The route crosses the Ru des Fagnes, a marshy river with no bridge in place in December 1944. The surrounding terrain is waterlogged, preventing further movement and impeding vehicle progress.20.

Two vehicles successfully cross the river and marshy meadow, halting 200 meters ahead to wait for the rest of the column. However, subsequent vehicles leave the track, attempting to cross the marshy fields, and become stuck in the mud up to their running gear. The first two tanks cautiously return but are unable to assist. German troops spend 90 minutes attempting to free the immobilized vehicles, but efforts fail. After 15 minutes, the two lead tanks abandon the effort and continue toward Ligneuville.

Later, Georg Preuss confirms that his company, advancing from Thirimont across open fields, encounters elements of the 14th U.S. Armored Battalion east of Ligneuville. After 30 minutes of combat, American resistance collapses, and Preuss reaches Ligneuville at 13:30, 45 minutes after Sternebeck’s Panzerspitze.

On December 18, German tanks return to recover the stranded vehicles, as confirmed by Stéphane Grosjean, a local eyewitness. Another witness, Henri Wansart, states that the first German tanks to reach Thirimont continue toward Bagatelle and the Baugnez crossroads, confirming that the initial vehicles were not Schützenpanzerwagen (SPW, half-tracks).21

Midday

Peiper’s forces reach Baugnez crossroads, south of Malmedy. At this location, Kampfgruppe Peiper intercepts a convoy of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion.

Baugnez, a small hamlet of eight or nine houses, was nearly deserted when Kampfgruppe Peiper arrived on Sunday, December 17, 1944. Located far from the West Wall, it had not been evacuated, but most residents had left for church in Malmedy. Only a few civilians remained, witnessing the events that followed 22.

12:30 – Halfway between Thirimont and Bagatelle, Peiper’s tanks spot American vehicles traveling south along N23. Upon reaching Baugnez crossroads, Peiper’s lead tanks encounter a U.S. convoy ascending from Ligneuville—Battery B, 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion. The engagement is brief. The American forces surrender without resistance, and 113 prisoners are assembled in a field beside the road. Kampfgruppe Peiper continues toward Ligneuville23.

14:00 – SS troops open fire without warning, executing 84 unarmed American prisoners. Some are shot while trying to flee, others are killed with pistol shots to the head. A few survivors feign death and later escape to report the massacre.

Malmedy Massacre

On December 17, 1944, near the Baugnez crossroads, southeast of Malmedy, Belgium, one of the most infamous war crimes of World War II unfolded. After ambushing a U.S. Army convoy from the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, Waffen-SS troops of Kampfgruppe Peiper took approximately 120 American prisoners. Instead of adhering to the rules of war, the SS lined up the unarmed POWs in a snowy field and opened fire with machine guns. Those who tried to escape were gunned down, while wounded survivors were executed with point-blank shots. In a final act of brutality, the SS set fire to a nearby café where some soldiers had sought refuge, killing all inside. The Malmedy Massacre became a defining atrocity of the Battle of the Bulge, symbolizing the ruthless nature of the Waffen-SS and fueling Allied resolve to hold them accountable.

Joachim Peiper after the war

On 16 July 1946, Joachim Peiper stood trial for war crimes. He was sentenced to death by hanging—a verdict later commuted to life imprisonment. After serving nearly 12 years, he was quietly released in 1956. Waiting for him was his wife, Sigurd Peiper, a former SS secretary, along with their three children. Peiper claimed he wanted to leave the war behind, but his actions told a different story.

Peiper found work at Porsche, a company that, like many in postwar Germany, had ties to former SS officers and Nazi officials. He remained closely linked to HIAG, the Mutual Help Association of Former Waffen-SS Members—a group dedicated to whitewashing the SS’s war crimes and rewriting history in favor of the perpetrators.

In the 1960s, he was investigated for the 1943 Boves massacre in Italy, where SS troops under his command had burned civilians alive in their homes. But with no surviving witnesses willing to testify, he was acquitted for lack of evidence.

By 1972, Peiper had withdrawn to Traves, France, a small village where he lived under his real name. But in 1974, his past caught up with him. A former French Resistance fighter recognized him and alerted the French Communist Party. Soon, newspapers published his location, and threats followed. On the night of 13 July 1976, Peiper’s house erupted in flames. He fired several shots in self-defense, but when the roof collapsed, he was trapped inside. The next day, authorities found a burned corpse, but the remains were so charred that identification was difficult.

Some believed he had staged his own death, escaping to South America or Spain under a new identity. Tabloids fed the speculation, publishing claims that the entire attack had been a diversion. Meanwhile, in Germany and France, right-wing extremists carried out reprisals, claiming Peiper had been murdered for his past.

Peiper leaves the scene before the execution begins, but as commander of Kampfgruppe Peiper, he bears responsibility for the actions of his unit. The Malmedy Massacre becomes one of the most infamous war crimes of the Battle of the Bulge24.

Afternoon

Ligneuville

13:00 – Kampfgruppe Peiper Reaches Ligneuville.

As the afternoon of December 17, 1944, unfolded, Kampfgruppe Peiper continued its relentless push westward through the Ardennes. The vanguard of the German force, commanded by Obersturmführer Werner Sternebeck, reached Ligneuville shortly after 13:00. The village lay eerily quiet—no American units were present in its center. Peiper, following his strategic directive to preserve key infrastructure, ordered that the bridge over the Amblève River remain intact. Engineers moved forward to inspect it, but suddenly, a burst of machine-gun fire shattered the silence. Several Germans fell wounded. Despite the engagement, American forces did not fire upon the German medics, who carried the injured away under the protective symbol of the Red Cross 25.

The town was lightly defended by elements of the 49th Antiaircraft Artillery Brigade, was unprepared for direct combat. At Hôtel du Moulin, Brigadier General Edward Timberlake, commander of the 49th AAA Brigade, had just finished lunch when a last-minute warning arrived. He and his staff fled toward Stavelot, escaping barely ten minutes ahead of Peiper’s vanguard 26.

The day before, Timberlake had been at the same hotel sharing an early dinner with Brigadier General William H. Hoge 27, commander of Combat Command B (CCB). They had been joined by 1st Lt. Raymond L. Lewis, a liaison officer returning from a mission to the 2nd Infantry Division. Lewis had reluctantly interrupted their meal to inform Hoge that General Middleton required him on the phone. As Hoge left to take the call, Timberlake invited Lewis to sit down and eat, and the young officer was impressed by the chef’s ability to transform standard U.S. Army ground beef into something extraordinary. Shortly after, Hoge placed CCB on ten-minute alert before departing at 18:00 28.

On the morning of December 17, Timberlake, in radio contact with one of his 90mm anti-aircraft batteries near Bütgenbach, learned of a breakthrough in the 99th Infantry Division’s sector. Anticipating trouble, he ordered his men to pack and be ready to leave Ligneuville at short notice 29. Timberlake had the time to destroy all vital documents at the command post, and to prepare its evacuation 30. The final order to evacuate came shortly after the noonday meal—just in time to avoid the rapid advance of Peiper’s column 31.

How did Peiper obtain information about the location of the 49th Anti-Aircraft Artillery headquarters?

Sternebeck’s accounts indicate that several American soldiers were captured between Büllingen and Thirimont, including a colonel, a captain, and a lieutenant. During their interrogation, Peiper learns from the colonel that General Timberlake has established the headquarters of the 49th Anti-Aircraft Artillery in Ligneuville. Acting on this intelligence, Peiper orders his vanguard to advance at full speed towards Ligneuville. Sternebeck receives this order while in radio communication with Peiper near the crossroads at Baugnez 32.

Captain Seymour Green, leading an improvised American force, moved toward Hôtel du Moulin to assess the situation. While en route, he encountered a Sherman M4 Tank Dozer speeding down the road. The vehicle had been returning from the 2nd Infantry Division to rejoin the 14th Tank Battalion, part of the 9th Armored Division’s Combat Command B, when it passed near Baugnez and came under fire from Peiper’s lead elements. The crew, having barely escaped the attack on Battery B’s convoy, withdrew rapidly toward Ligneuville 33. Captain Green, still assessing the situation, instructed his driver to remain behind while he proceeded on foot. As he rounded a bend in the road, he unexpectedly came face to face with a German tank. The sudden encounter left him momentarily frozen before he discarded his carbine and surrendered 34.

Meanwhile, just outside the town, a small group of stragglers from the 14th Tank Battalion remained as Peiper’s lead tanks approached.

These troops, moving from the Malmedy area toward Sankt Vith, had two Shermans—one of which was an M4A3 equipped with the newer 76mm M1 gun—and an M10 tank destroyer. Positioned on a hill overlooking the highway, they were engaged in maintenance when the M4 Tank Dozer, which had retreated earlier, joined them 35.

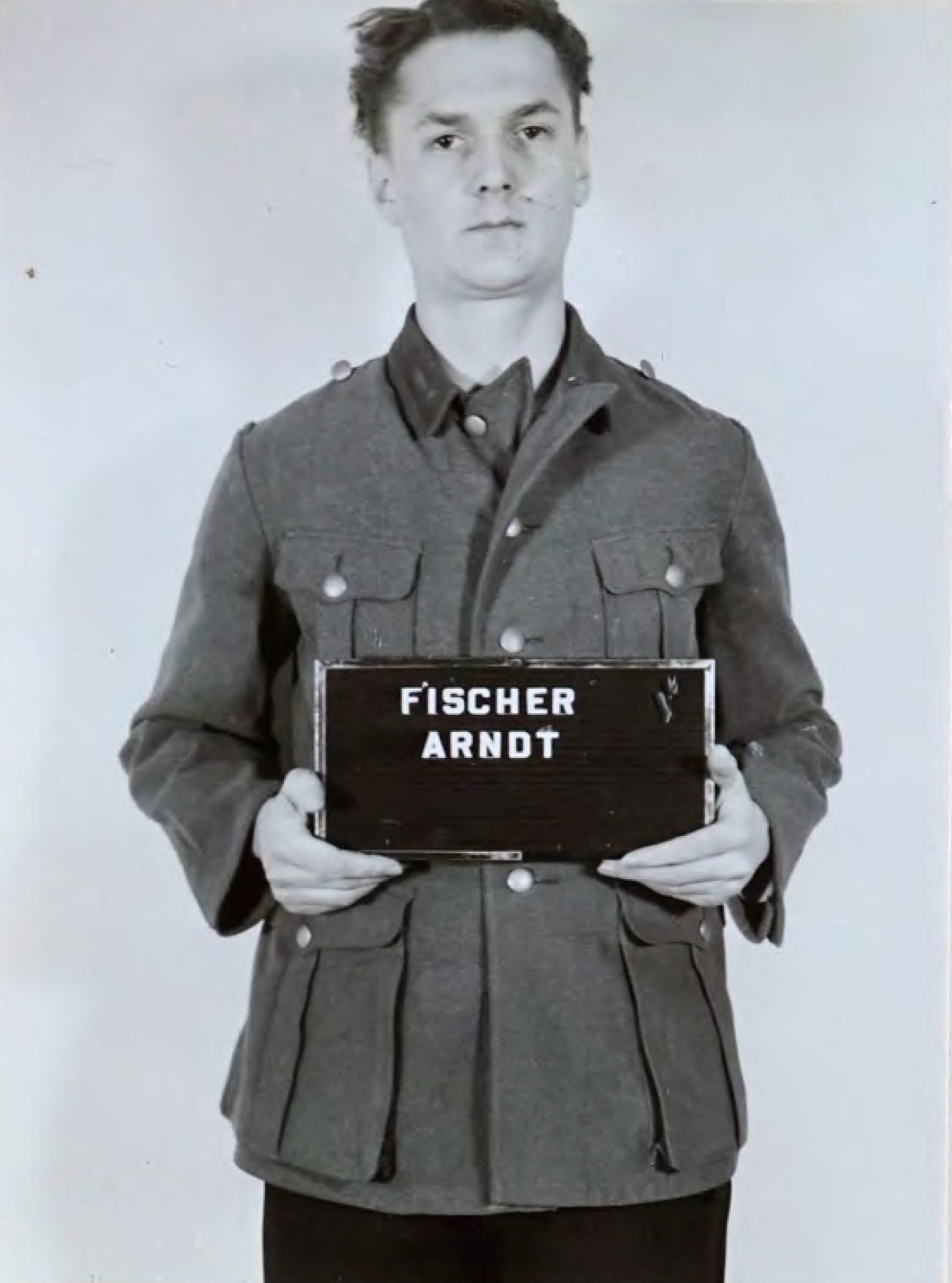

Panther 152 in Ligneuville

As the first German tank appeared— Panther 152 from SS-Panzer Regiment 1, LSSAH—it was struck by a 76mm round from the M4 Tank Dozer. Panther 152 was commanded by SS-Untersturmführer Arndt Fischer. The shell penetrated the rear armor, killing the driver, SS-Panzergrenadier Wolfgang Simon, instantly. The impact ignited the tank, leaving Fischer severely burned. SS-Rottenführer Josef Duda, the gunner, along with SS-Panzergrenadiers Gunter Weseman and Gunter Ikrat, the loader and radio operator respectively, managed to escape. Seeking cover near the Hôtel des Ardennes, Peiper’s driver halted a half-track while Peiper dismounted to assist in treating Fischer’s wounds.36

The tank was commanded by SS-Untersturmführer Arndt Fischer. The shell penetrated the rear armor, killing the driver, SS-Panzergrenadier Wolfgang Simon, instantly. The impact ignited the tank, leaving Fischer severely burned. SS-Rottenführer Josef Duda, the gunner, along with SS-Panzergrenadiers Gunter Weseman and Gunter Ikrat, the loader and radio operator respectively, managed to escape 37. Seeking cover near the Hôtel des Ardennes, Peiper’s driver halted a half-track while Peiper dismounted to assist in treating Fischer’s wounds.38

Arndt Fischer, born in 1921, had been a member of the SS since February 20, 1939, and was 23 years old during the Ardennes Offensive. After the war, Fischer was prosecuted during the Malmedy Trials, where the prosecution presented evidence that he had aided in transmitting the order to company commanders of the 1st Battalion to execute prisoners of war and Allied civilians on or about December 15, 1944. He was further accused of being responsible for such executions between December 16, 1944, and January 13, 1945. Fischer was found guilty and sentenced to 15 years in prison 39.

The Panther 152 was still there when the Americans recaptured the town, although air liaison officers—Major Albert Triers, Major William Abbot, and 1st Lieutenant Richard Zimbowski—attempted to claim it as a kill by the Ninth Air Force 41.

Frustrated by the loss of an officer he regarded as a friend Peiper attempted to take direct action. Grabbing a Panzerfaust, he moved toward the American tankdozer, intending to destroy it. Before he could reach his target, however, a round from a German tank inadvertently struck the tankdozer, disabling it 42.

The German column then proceeded to neutralize the two immobilized American Shermans and the assault gun. Recognizing the need to secure the town before advancing further, Peiper ordered SS-Panzergrenadiers to clear Ligneuville while he briefly entered the Hôtel du Moulin. There, he spent approximately half an hour consuming food left behind by Timberlake and his staff 43.

With Ligneuville under German control, Peiper turned his attention to the next phase of his advance. His objective was to reach a road west of town that led directly to Stavelot. Though this route technically encroached on the 12th SS Panzer Division’s designated sector, it provided better mobility than the road assigned to him farther south. Lacking radio communication with his divisional headquarters, Peiper assumed from the absence of significant combat noise in Malmédy that the 12th SS Panzer Division was still lagging behind. He planned to reach Trois-Ponts after Stavelot, where he would rejoin his assigned route. Trois-Ponts, named for its three bridges spanning the Amblève and Salm Rivers, was a crucial crossing point. From there, he intended to advance to Werbomont, which lay on the north-south Bastogne-Liège highway. If successful, this maneuver would allow him to bypass the worst of the Ardennes terrain and secure a relatively direct route to the Meuse River at Huy, approximately twenty-five miles beyond Werbomont 44.

Peiper’s men swiftly overran the American command post, capturing multiple officers—eight were executed on the spot. Peiper then established a temporary headquarters at Hôtel du Moulin, where his men ate, drank, and looted the surrounding area 45.

As Peiper consolidated his hold on the town, Obersturmführer Arndt Fischer’s Panther was knocked out by a Sherman during a brief skirmish south of Ligneuville. The engagement involved elements of Combat Command Reserve (CCR), 7th Armored Division, attempting to slow the German advance 46.

At the Amblève bridge, German combat engineers searched for demolition charges, aiming to cut off potential American reinforcements. A temporary ceasefire followed as both sides evacuated their wounded 47.

With Ligneuville secured, Peiper remained in the town, meeting with SS-Oberführer Wilhelm Mohnke, commander of the 1. SS-Panzer-Division, to assess the next phase of the advance 48.

The War Crimes in Ligneuville

Eight GIs from Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, surrendered and were executed—shot in the back of the neck 49.

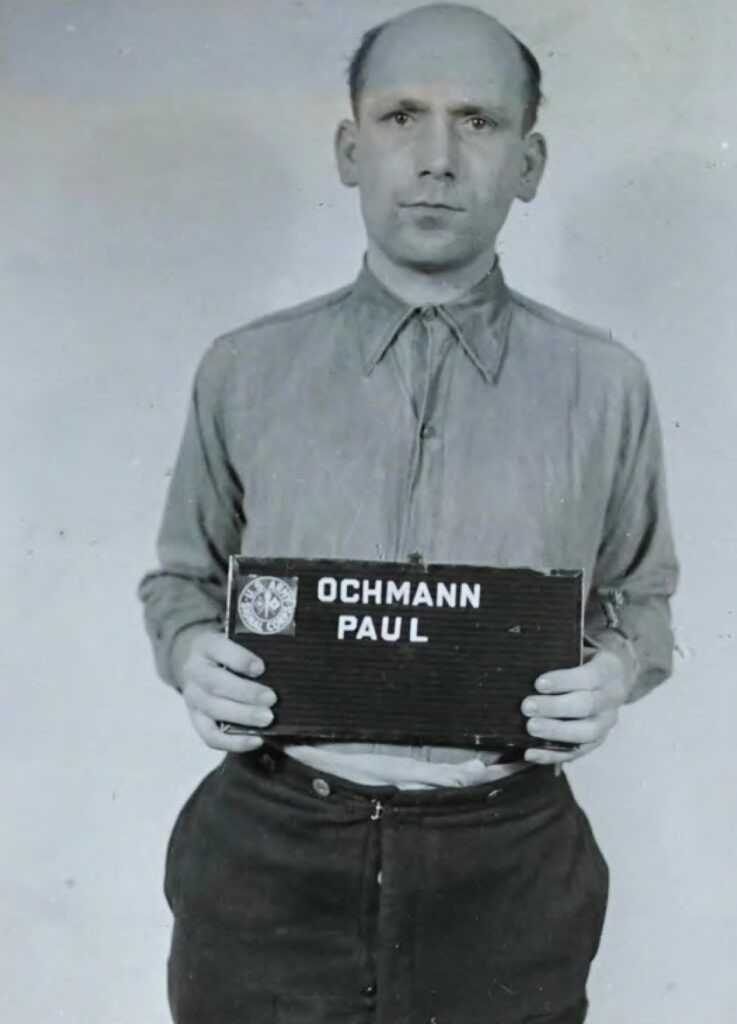

A witness, Marie Lochen, saw the events unfold. While tending her cattle, she observed about thirty captured GIs being escorted by SS men. SS-Oberscharführer Paul Ochmann and SS-Sturmmann Suess, both from the 9. Kompanie, SS-Panzer-Pionier-Bataillon 1, selected eight prisoners at random. They ordered them to march, hands on their heads, toward a path lined with an embankment 50.

Ochmann positioned them with their backs turned. The location was intentional—shots from behind would send the bodies tumbling down the slope. He executed four or five with a pistol. Suess killed the remaining prisoners using the same method 51.

At the Hôtel du Moulin, Ochmann confronted additional captives, including Captain Green. “Tuez-les!” ordered an SS officer. The hotel’s owner, M. Rupp, attempted to intervene, but Ochmann struck him repeatedly 52.

An abrupt intervention halted the executions. Another SS officer entered and ordered, “Il suffit! Laissez ces hommes en paix! À votre poste immédiatement!” Ochmann obeyed. Seizing the opportunity, Rupp rushed to the cellar and offered alcohol to the SS men. The remaining prisoners were spared 53.

22 American soldiers from the 14th Tank Battalion, 9th Armored Division,

Company B, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, 9th Armored Division, US Army

were captured and marched to the Hôtel du Moulin, which Peiper had selected as his temporary headquarters 54.

Upon arrival at Hôtel du Moulin, eight captured American soldiers were separated from the group and led to the side of the hotel. There, SS-Hauptscharführer Paul Ochmann, a 32-year-old officer from the 1. Bataillon, SS-Panzer-Regiment 1, Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, and another SS-Unteroffizier executed them.

Madame Marie Lochem, a Belgian civilian tending her cows in a nearby barn, witnessed the massacre. She saw Ochmann line up the prisoners and shoot them one by one in the head. All eight men were murdered at close range after surrendering, making this a clear violation of the laws of war.

According to later testimonies, some were forced to kneel before being shot at point-blank range, the executioners placing their pistols in the mouths of the victims.

From the kitchen window, Rupp watched in horror as SS-Hauptscharführer Paul Ochmann forced eight captured American soldiers into the yard. Without hesitation, Ochmann raised his pistol and began executing them one by one.

For years, the hotel’s owner, Peter Rupp, had lived a double life. Publicly, he catered to German officers; secretly, as “Monsieur Kramer,” he worked with the Belgian White Army resistance, sheltering Allied airmen before smuggling them through the underground network. At least 22 American, British, and French airmen owed their lives to him. On this 17 December, But Rupp wasn’t finished.

Inside the hotel, fourteen more American prisoners were being held at gunpoint, awaiting a similar fate. Thinking fast, Rupp used his reputation and his store of fine wine and cognac to distract the SS guards. As the officers drank, the executions were delayed—and eventually abandoned 55. Thanks to Rupp’s intervention, fourteen Americans survived that night.

Desperate to prevent further killings, he attempted to reason with a German NCO. Inside the hotel, fourteen more American prisoners awaited what seemed to be an inevitable fate. Realizing that direct intervention was impossible, Rupp resorted to deception. He used his reputation and stock of fine wine and cognac to distract the SS guards, delaying the executions. As the officers drank, the killings were postponed—and ultimately abandoned 56.

The victims were Staff Sergeant Lincoln Abraham (29) 57, Technician 5th Grade John M Borcina (27), Staff Sergeant Joseph Collins (32), Private First Class Michael Penney (22) 58, Technician 4th Grade Casper Johnson (25), Private Clifford Pitts (36), Private Gerald Carter (37), and Private Nick Sullivan (22). Initially, Abraham’s name was incorrectly inscribed as “Abraham Lincoln” on the memorial, but this was later corrected when the site was refurbished.

After the war, Lincoln Abraham, Gerald Carter, and Nick Sullivan were repatriated to the United States for reburial. The other five—Borcina, Collins 59, Penney, Johnson, and Pitts—were laid to rest at Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery in Belgium 60 61 62.

Today, a memorial near the Hôtel du Moulin in Ligneuville honors these eight men, victims of Kampfgruppe Peiper’s war crimes 63.

Investigation of the Malmedy Massacre

Following the war, Paul Ochmann was tried for executing American prisoners in Ligneuville. In an extrajudicial confession, he admitted to personally shooting four or five unarmed POWs in the neck while a subordinate executed the others. His confession was corroborated by Walter Fransee, a soldier from the 1. Panzergrenadier-Division, who testified that Ochmann had sought assistance in carrying out the executions. At trial, American interrogator Lt. Perl stated that Ochmann’s confession was given voluntarily, without coercion. However, posttrial statements challenged this claim. Ochmann later asserted he had been subjected to physical abuse, prolonged detention, and psychological pressure, compelling him to sign a fabricated confession. Fransee, who initially testified against him, also retracted his statement, claiming it had been obtained under duress. The Simpson Report and the Administration of Justice Review Board, which investigated the Malmedy Trials, documented instances of prisoner mistreatment during interrogations. While the Judge Advocate recommended the death penalty, the reviewing officer determined that the lack of sufficient corroborating evidence—beyond contested statements—precluded its imposition. Despite overwhelming indications of guilt, Ochmann’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment—not out of clemency, but due to legal concerns over the methods used to obtain key evidence 64.

After a two-hour halt in Ligneuville for reorganization, Kampfgruppe Peiper resumes its advance westward. The column moves unopposed through the villages of Pont and Beaumont 65 66.

Sources Ligneuville chapter:

Toland, John. “The Brave Innkeeper of ‘The Bulge’.” Coronet, vol. 47, no. 2, Dec. 1959, pp. 158–163. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/sim_coronet_1959-12_47_2_0. Accessed 16 Mar. 2025.

Pont

Evening

Kampfgruppe Peiper reached Stavelot in the late afternoon.

Stavelot

Kampfgruppe Peiper reached the outskirts of Stavelot as dusk settled over the Ardennes. The town, which had spent the day in uneasy quiet, was about to become a battleground.

Based on the personal recollections of Guy Lebeau, a young resident of Stavelot during the battle. His memories were preserved and shared through Henri Rogister 67.

Morning: Unease in Stavelot

08:00 – A U.S. roadblock is hastily established in town, with two American soldiers crouched behind a machine gun facing southwest toward Trois-Ponts. Civilians exchange nervous glances—why defend that direction when the real danger lies to the east? At the Amblève River bridge, similar positions suggest the Americans are securing key crossings, but there’s a growing sense of disarray .

09:30 – Without warning, the roadblock is abandoned. The soldiers have vanished. No explanation, no orders relayed. Stavelot is suddenly exposed 68.

10:30 – U.S. tanks appear, rumbling through town toward Trois-Ponts. The movement is constant—7th Armored Division units pushing forward, their crews grim-faced. To some, it looks like reinforcement; to others, a prelude to retreat 69.

Afternoon: The Exodus Begins

14:00–17:00 – The Stavelot garrison begins to dissolve. These are not frontline troops—logisticians, engineers, and military police—now hastily evacuating. Whispers spread: German paratroopers may have landed west of town. Fear tightens its grip 70.

Evening: The Last Warning

18:00 – Refugees stagger in from the east, faces drawn with exhaustion. “The Germans are coming.” Burgomaster Arnold Godin wastes no time—he orders a curfew. Doors are bolted, windows shuttered 71.

20:00 – More troubling reports: German forces have reached Lodomez. Civilians, sensing the inevitable, descend into cellars with whatever they can carry—mattresses, blankets, food. The walls of their homes will be their last line of defense 72.

Nightfall: The Silence Before the Storm

Distant gunfire cracks through the night. No one knows where it’s coming from—or how soon it will reach them. In the cellars of Stavelot, sleep is impossible. The battle is coming

Throughout the day, Stavelot remains calm. However, after Sunday mass, engine noises are heard as American armored vehicles from the 7th Armored Division move through town toward Trois-Ponts.

Kampfgruppe Peiper reached the outskirts of Stavelot as dusk settled over the Ardennes. The town, which had spent the day in uneasy quiet, was about to become a battleground.

08:00 – A U.S. roadblock is set up in Stavelot, with two GIs manning a machine gun positioned toward Trois-Ponts (southwest). The placement raises concerns among civilians, as the frontline is to the east. Similar defensive positions are reported at the Amblève River bridge, suggesting that roads from Malmedy and Francorchamps may have been similarly secured 73.

Morning: Unease in Stavelot

08:00 – A U.S. roadblock is hastily established in town, manned by two GIs with a machine gun facing southwest toward Trois-Ponts. Civilians exchange nervous glances—why defend that direction when the real danger lies to the east? At the Amblève River bridge, similar positions suggest the Americans are securing key crossings, but there’s a growing sense of disarray 74.

09:30 – The roadblock is abandoned, and the GIs are gone 75.

10:30 – U.S. tanks arrive, moving toward Trois-Ponts from Francorchamps and Malmedy. The 7th Armored Division passes through the town continuously throughout the day 76.

14:00–17:00 – The Stavelot garrison, composed mostly of non-combat support units (logistics, engineering, maintenance, military police), begins evacuating. Reports indicate that German paratroopers may have been dropped west of Stavelot, heightening concerns among civilians 77.

18:00 – Belgian refugees arrive from the east, warning that German forces are returning. The Burgomaster, Arnold Godin, imposes a curfew 78.

20:00 – Reports emerge that German troops have reached Lodomez. Civilians prepare for an extended stay in cellars, bringing mattresses, blankets, clothing, and food 79.

Evening – Gunfire is heard in the distance, increasing anxiety among residents. Civilians struggle to sleep, uncertain about the unfolding situation 80.

09:30 – Without warning, the roadblock is abandoned. The soldiers have vanished. No explanation, no orders relayed. Stavelot is suddenly exposed 81.

Afternoon: The Exodus Begins

10:30 – U.S. tanks appear, rumbling through town toward Trois-Ponts. The movement is constant—7th Armored Division units pushing forward, their crews grim-faced. To some, it looks like reinforcement; to others, a prelude to retreat 82.

14:00–17:00 – The Stavelot garrison begins to dissolve. These are not frontline troops—logisticians, engineers, and military police—now hastily evacuating. Whispers spread: German paratroopers may have landed west of town. Fear tightens its grip 83.

Evening: The Last Warning

18:00 – Refugees stagger in from the east, faces drawn with exhaustion. “The Germans are coming.” Burgomaster Arnold Godin wastes no time—he orders a curfew. Doors are bolted, windows shuttered 84.

20:00 – More troubling reports: German forces have reached Lodomez. Civilians, sensing the inevitable, descend into cellars with whatever they can carry—mattresses, blankets, food. The walls of their homes will be their last line of defense 85.

Nightfall: The Silence Before the Storm

Distant gunfire cracks through the night. No one knows where it’s coming from—or how soon it will reach them. In the cellars of Stavelot, sleep is impossible. The battle is coming.

In the afternoon – U.S. engineers set up roadblocks south of Stavelot in anticipation of the German advance.

16:30 – Kampfgruppe Peiper arrives at Stavelot, attempting to cross the Amblève River.

The bridge over the Amblève River was still intact, making it a vital crossing point.

18:30 – Sergeant Hensel from the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion installs a minefield on the Corniche road leading into Stavelot.

19:30 – The roadblock is attacked by German infantry, possibly supported by tanks. Hensel and his men retreat.

First attack on Stavelot:

Peiper’s lead tanks moved into town but encountered fierce resistance from American troops.

The 291st Engineer Battalion and elements of the 30th Infantry Division fought house to house.

The bridge was nearly lost, but American forces held on.

Peiper’s unit stalled in Stavelot for the night, unable to secure the river crossing .

21:00 – Hensel reaches La Gleize and reports the attack, but his warning is not acted upon immediately.

22:45 – U.S. high command is notified of the imminent threat to Stavelot, but no immediate defensive actions are taken.

Monday, December 18, 1944

Investigation of the Malmedy Massacre

As the Battle of the Bulge concluded with a German defeat, Allied forces launched investigations into the massacre of American prisoners of war. Early inquiries identified Kampfgruppe Peiper as the unit responsible for the Malmedy massacre, though its personnel were dispersed across prison camps, hospitals, labor detachments, and even the United States86.

Challenges in Interrogation

Investigators quickly encountered difficulties in questioning the accused, as inadequate security in prison camps allowed suspects to rejoin their comrades and coordinate their statements after interrogation87. It was also discovered that before the Ardennes Offensive, SS troops had been sworn to secrecy regarding orders to execute prisoners of war88.

To improve interrogation effectiveness, all Kampfgruppe Peiper members were transferred to an internment camp at Zuffenhausen, but initial barracks-style housing still allowed communication between prisoners, further complicating the investigation89.

The Blame on Major Poetschke

During this period, evidence emerged that Joachim Peiper had instructed his men to blame the Malmedy massacre on Major Werner Poetschke, who had been killed in Austria during the war’s final days. Peiper’s subordinates carefully followed this directive, making it difficult to assign individual responsibility90.

Interrogation at Schwäbisch Hall

To ensure strict isolation during questioning, key suspects were relocated to the Schwäbisch Hall interrogation center, a modern German prison where detainees were kept in individual cells91. The initial transfer included over 400 prisoners, with additional transfers continuing through March 194692.

It was during interrogations at Schwäbisch Hall that allegations of prisoner mistreatment emerged, later influencing the legal proceedings of the Malmedy Trials93.

Source: 94.

Footnotes

- Pallud, Jean-Paul. Ardennes, 1944: Peiper and Skorzeny. Osprey Publishing, 1987.

- Pallud, Jean-Paul. Ardennes, 1944: Peiper and Skorzeny. Osprey Publishing, 1987.

- Parker, Danny S. Peiper’s Last Gamble: Hitler’s Panzer Spearhead in the Battle of the Bulge, December 1944. 1st ed., Pen & Sword Books Limited, 2025.

- Parker, Danny S. Peiper’s Last Gamble: Hitler’s Panzer Spearhead in the Battle of the Bulge, December 1944. 1st ed., Pen & Sword Books Limited, 2025.

- Parker, Danny S. Peiper’s Last Gamble: Hitler’s Panzer Spearhead in the Battle of the Bulge, December 1944. 1st ed., Pen & Sword Books Limited, 2025.

- www.lexikon-der-wehrmacht.de

- Baily, Charles M., et al. Anti-Armor Defense Data Study (A2D2), Phase II, Final Report, Vol. IV: U.S. Anti-Tank Defense at Krinkelt-Rocherath, Belgium (December 1944). Science Applications International Corp., Feb. 15, 1991.

- Baily, Charles M., et al. Anti-Armor Defense Data Study (A2D2), Phase II, Final Report, Vol. IV: U.S. Anti-Tank Defense at Krinkelt-Rocherath, Belgium (December 1944). Science Applications International Corp., Feb. 15, 1991.

- Baily, Charles M., et al. Anti-Armor Defense Data Study (A2D2), Phase II, Final Report, Vol. IV: U.S. Anti-Tank Defense at Krinkelt-Rocherath, Belgium (December 1944). Science Applications International Corp., Feb. 15, 1991.

- Baily, Charles M., et al. Anti-Armor Defense Data Study (A2D2), Phase II, Final Report, Vol. IV: U.S. Anti-Tank Defense at Krinkelt-Rocherath, Belgium (December 1944). Science Applications International Corp., Feb. 15, 1991.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: Hiver 1944-1945. Éditions Racine, 2006.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: Hiver 1944-1945. Éditions Racine, 2006.

- Schrijvers, Peter. The Unknown Dead: Civilians in the Battle of the Bulge. University Press of Kentucky, 2005.

- Schrijvers, Peter. The Unknown Dead: Civilians in the Battle of the Bulge. University Press of Kentucky, 2005.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: Hiver 1944-1945. Éditions Racine, 2006.

- Wynn, Stephen. Joachim Peiper and the Nazi Atrocities of 1944. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military, 2022

- KRAFT DE LA SAULX, Christian (ed.). La Bataille des Ardennes. p. 49.

- KRAFT DE LA SAULX, Christian (ed.). La Bataille des Ardennes. p. 50.

- Grégoire, Gérard. Les Panzer de Peiper face à l’U.S. Army. Stavelot: J. Chauveheid, 1986.

- Grégoire, Gérard. Les Panzer de Peiper face à l’U.S. Army. Stavelot: J. Chauveheid, 1986.

- Cuppens, Gerd. Massacre à Malmedy? Ardennes: 17 décembre 1944. Le Kampfgruppe Peiper dans les Ardennes. Bayeux: Éditions Heimdal, 1989

- Schrijvers, Peter. The Unknown Dead: Civilians in the Battle of the Bulge. University Press of Kentucky, 2005.

- Pallud, Jean-Paul. Ardennes Album Memorial. Bayeux: Heimdal, 1986.

- Wynn, Stephen. Joachim Peiper and the Nazi Atrocities of 1944. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military, 2022.

- Cuppens, Gerd. Massacre à Malmedy ? Ardennes : 17 décembre 1944. Le Kampfgruppe Peiper dans les Ardennes. Éditions Heimdal, 1989

- Grégoire, Gérard. Les Panzer de Peiper face à l’U.S. Army. Stavelot: J. Chauveheid, 1986.

- William Morris Hoge (13 January 1894 – 29 October 1979)

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- Bergstrom, Christer. The Ardennes, 1944-1945: Hitler’s Winter Offensive. Casemate / Vaktel Forlag, 2015

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- Cuppens, Gerd. Massacre à Malmedy? Ardennes: 17 décembre 1944. Le Kampfgruppe Peiper dans les Ardennes. Éditions Heimdal, 1989.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- Bergstrom, Christer. The Ardennes, 1944-1945: Hitler’s Winter Offensive. Casemate / Vaktel Forlag, 2015.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- Parker, Danny S. Fatal crossroads: the untold story of the Malmédy Massacre at the Battle of the Bulge. Da Capo Press, 2012.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- United States. War Department. Malmedy Trial: Volume 7, Appendix B-F. U.S. Military Legal Resources, Library of Congress, maint.loc.gov. Accessed 16 Mar. 2025

- “Panther Ausführung G with Tactical Number 152 of SS-Panzer Regiment 1, Kampfgruppe Peiper.” The King of La Gleize, 2019. Facebook post. .

- “Panther Ausführung G with Tactical Number 152 of SS-Panzer Regiment 1, Kampfgruppe Peiper.” The King of La Gleize, 2019. Facebook post. .

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- Gillet, 2003.

- Gillet, 2003.

- Gillet, 2003.

- Pallud, Jean-Paul. Ardennes, 1944: Peiper and Skorzeny. Elite Series 11. London: Osprey Publishing, 1987.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: hiver 1944-1945. Ed. Racine, 2006.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: hiver 1944-1945. Ed. Racine, 2006.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: hiver 1944-1945. Ed. Racine, 2006.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: hiver 1944-1945. Ed. Racine, 2006.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: hiver 1944-1945. Ed. Racine, 2006.

- Liberation Route Europe, www.liberationroute.com/pois/1857/memorial-to-the-murdered-us-soldiers-lingneuville

- Source: “The Brave Innkeeper” – World War Media https://www.worldwarmedia.com/2016/09/15/thebraveinnkeeper/

- Source: “The Brave Innkeeper” – World War Media

- https://fr.findagrave.com/memorial/11478645/lincoln-abraham

- http://wartimeheritage.com/whaww2ns6/wwii_penney_michael_bernard.htm

- D, Row 15, Grave 33

- Liberation Route Europe, www.liberationroute.com/pois/1857/memorial-to-the-murdered-us-soldiers-lingneuville

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. New York: Morrow, 1984, p. 228

- Traces of War, www.tracesofwar.com/sights/982/Memorial-US-9th-Armoured-Division.htm

- Traces of War, www.tracesofwar.com/sights/982/Memorial-US-9th-Armoured-Division.htm

- United States. War Department. Malmedy Trial: Volume 7, Appendix K-P. U.S. Military Legal Resources, Library of Congress, maint.loc.gov. Accessed 16 Mar. 2025.

- Pallud, Jean-Paul. Ardennes, 1944: Peiper and Skorzeny. Elite Series 11. London: Osprey Publishing, 1987.

- Heyden, 2021

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes. Investigation of the Malmedy Massacre. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949, p. 2.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 3.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 5.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 6.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 7.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 8.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 9.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 10.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes. Investigation of the Malmedy Massacre. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949. Available at: tile.loc.gov