Ligneuville

The 49th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Brigade in Ligneuville

Allied Dispositions in the Bullange Sector – December 16, 1944

The Bullange sector was defended by units of V Corps, commanded by Major General Leonard T. Gerow. The frontline positions were held by the 393rd and 394th Infantry Regiments, both part of the 99th Infantry Division.

To the south, in the Lanzerath-Losheim sector, elements of the 14th Cavalry Group, attached to the 1st Infantry Division, were deployed in a screening role.

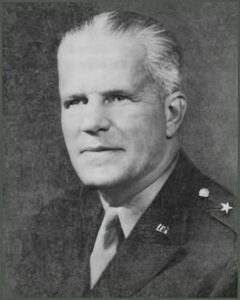

In Ligneuville, the 49th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Brigade, under the command of Brigadier General Edward J. Timberlake, was deployed in the “Diver Belt” defense system, an anti-V1 configuration (“Diver” being the Allied code for V1 rockets). Its batteries were positioned for air defense and were not integrated into the sector’s ground combat formations (Grégoire, 1986).

Brigadier General Edward “Big Ed” Timberlake was stationed at Hôtel du Moulin, near the northern edge of Ligneuville, along with his staff (Thomas 2012; Wenkin 2024).

In the months leading up to the Battle of the Bulge, the 49th AAA Brigade played a critical role in securing Allied positions across Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Tasked with air defense and tactical support for ground forces, the brigade was responsible for protecting logistical hubs, river crossings, and command installations from aerial attacks, particularly against V-1 flying bombs (Kelakos et al., The Forty-Niners).

Following the rapid Allied advance through France and Belgium, the 49th AAA Brigade relocated its command post to Château de Namur in September 1944, taking control of anti-aircraft defenses along the Meuse River crossings from Dinant to Maastricht. This defensive network ensured the security of supply lines and helped prevent Luftwaffe air raids on critical infrastructure.

The brigade’s firepower was distributed among the 2nd, 11th, 16th, and 18th AAA Groups, which commanded twelve AAA battalions. As the Allied front pushed eastward, the brigade expanded its area of responsibility, securing Luxembourg and Verviers during the autumn of 1944 (Kelakos et al., The Forty-Niners).

Relocation to Ligneuville

By late October 1944, in preparation for further operations, the 49th AAA Brigade moved its command post to Ligneuville, closer to the front lines. The town, historically a hunting retreat, was strategically located near the German border and housed a population with a significant German heritage (Kelakos et al., The Forty-Niners). This repositioning ensured a centralized command structure for anti-aircraft operations in the region.

Throughout November, brigade personnel engaged with both local residents and former Wehrmacht officers, including General von Falkenstein, an associate of Field Marshals von Rundstedt and Model. They also developed contacts within the Belgian resistance (Armée Blanche), forging relationships with key operatives such as an adjutant known as “Nick” (Kelakos et al., The Forty-Niners).

With the increasing threat of V-1 flying bombs, particularly targeting Liège, Verviers, and Spa, the brigade reinforced its “Diver Belt” defense system in November. The 11th AAA Group deployed gun battalions along the front lines, supported by automatic weapons batteries, in an effort to intercept incoming V-1s before they reached Allied-controlled areas (Kelakos et al., The Forty-Niners).

By December, the 49th AAA Brigade’s responsibilities stretched across five countries—France, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany—defending key installations and providing continuous air defense support for advancing Allied forces (Kelakos et al., The Forty-Niners).

While Thanksgiving and Christmas preparations were underway in Ligneuville, reports suggested that both Volksgrenadier divisions and Allied troops were using the sector primarily for training and rotations. The assumption that the terrain’s dense forests and rugged hills made large-scale attacks unlikely led to a false sense of security among American commanders (Kelakos et al., The Forty-Niners).

Saturday, December 16, 1944

This perception was shattered on 16 December 1944, when the Germans launched a massive artillery barrage, marking the beginning of their Ardennes counteroffensive. The 49th AAA Brigade headquarters was thrown into emergency action as V-1 flying bomb attacks surged in parallel with the ground assault. Prisoners captured by the 106th Infantry Division confirmed that this was not a feint but a major German offensive (Kelakos et al., The Forty-Niners).

Liaison officers worked to maintain contact with the 99th and 106th Infantry Divisions, but intelligence reports remained scarce, offering little clarity on enemy troop movements. Despite the rapidly deteriorating situation, Army Headquarters instructed the brigade to hold its position, setting the stage for the fierce engagements that would follow in the Battle of the Bulge (Kelakos et al., The Forty-Niners).

Sunday, December 17, 1944

13:00 – Kampfgruppe Peiper Reaches Ligneuville.

As the afternoon of December 17, 1944, unfolded, Kampfgruppe Peiper continued its relentless push westward through the Ardennes. The vanguard of the German force, commanded by Obersturmführer Werner Sternebeck, reached Ligneuville shortly after 13:00. The village lay eerily quiet—no American units were present in its center. Peiper, following his strategic directive to preserve key infrastructure, ordered that the bridge over the Amblève River remain intact. Engineers moved forward to inspect it, but suddenly, a burst of machine-gun fire shattered the silence. Several Germans fell wounded. Despite the engagement, American forces did not fire upon the German medics, who carried the injured away under the protective symbol of the Red Cross 1.

The town was lightly defended by elements of the 49th Antiaircraft Artillery Brigade, was unprepared for direct combat. At Hôtel du Moulin, Brigadier General Edward Timberlake, commander of the 49th AAA Brigade, had just finished lunch when a last-minute warning arrived. He and his staff fled toward Stavelot, escaping barely ten minutes ahead of Peiper’s vanguard 2.

The day before, Timberlake had been at the same hotel sharing an early dinner with Brigadier General William H. Hoge 3, commander of Combat Command B (CCB). They had been joined by 1st Lt. Raymond L. Lewis, a liaison officer returning from a mission to the 2nd Infantry Division. Lewis had reluctantly interrupted their meal to inform Hoge that General Middleton required him on the phone. As Hoge left to take the call, Timberlake invited Lewis to sit down and eat, and the young officer was impressed by the chef’s ability to transform standard U.S. Army ground beef into something extraordinary. Shortly after, Hoge placed CCB on ten-minute alert before departing at 18:00 4.

On the morning of December 17, Timberlake, in radio contact with one of his 90mm anti-aircraft batteries near Bütgenbach, learned of a breakthrough in the 99th Infantry Division’s sector. Anticipating trouble, he ordered his men to pack and be ready to leave Ligneuville at short notice 5. Timberlake had the time to destroy all vital documents at the command post, and to prepare its evacuation 6. The final order to evacuate came shortly after the noonday meal—just in time to avoid the rapid advance of Peiper’s column 7.

A small group of stragglers from the 14th Tank Battalion of 9th Armored Division’s Combat Command B—en route from the Malmédy area to Sankt Vith—remained in the town as the leading SS tanks approached (Bergstrom 2015).

How did Peiper obtain information about the location of the 49th Anti-Aircraft Artillery headquarters?

Sternebeck’s accounts indicate that several American soldiers were captured between Büllingen and Thirimont, including a colonel, a captain, and a lieutenant. During their interrogation, Peiper learns from the colonel that General Timberlake has established the headquarters of the 49th Anti-Aircraft Artillery in Ligneuville. Acting on this intelligence, Peiper orders his vanguard to advance at full speed towards Ligneuville. Sternebeck receives this order while in radio communication with Peiper near the crossroads at Baugnez 8.

Captain Seymour Green, leading an improvised American force, moved toward Hôtel du Moulin to assess the situation. While en route, he encountered a Sherman M4 Tank Dozer speeding down the road. The vehicle had been returning from the 2nd Infantry Division to rejoin the 14th Tank Battalion, part of the 9th Armored Division’s Combat Command B, when it passed near Baugnez and came under fire from Peiper’s lead elements. The crew, having barely escaped the attack on Battery B’s convoy, withdrew rapidly toward Ligneuville 9. Captain Green, still assessing the situation, instructed his driver to remain behind while he proceeded on foot. As he rounded a bend in the road, he unexpectedly came face to face with a German tank. The sudden encounter left him momentarily frozen before he discarded his carbine and surrendered 10.

These troops, moving from the Malmedy area toward Sankt Vith, had two Shermans—one of which was an M4A3 equipped with the newer 76mm M1 gun—and an M10 tank destroyer. Positioned on a hill overlooking the highway, they were engaged in maintenance when the M4 Tank Dozer, which had retreated earlier, joined them 11.

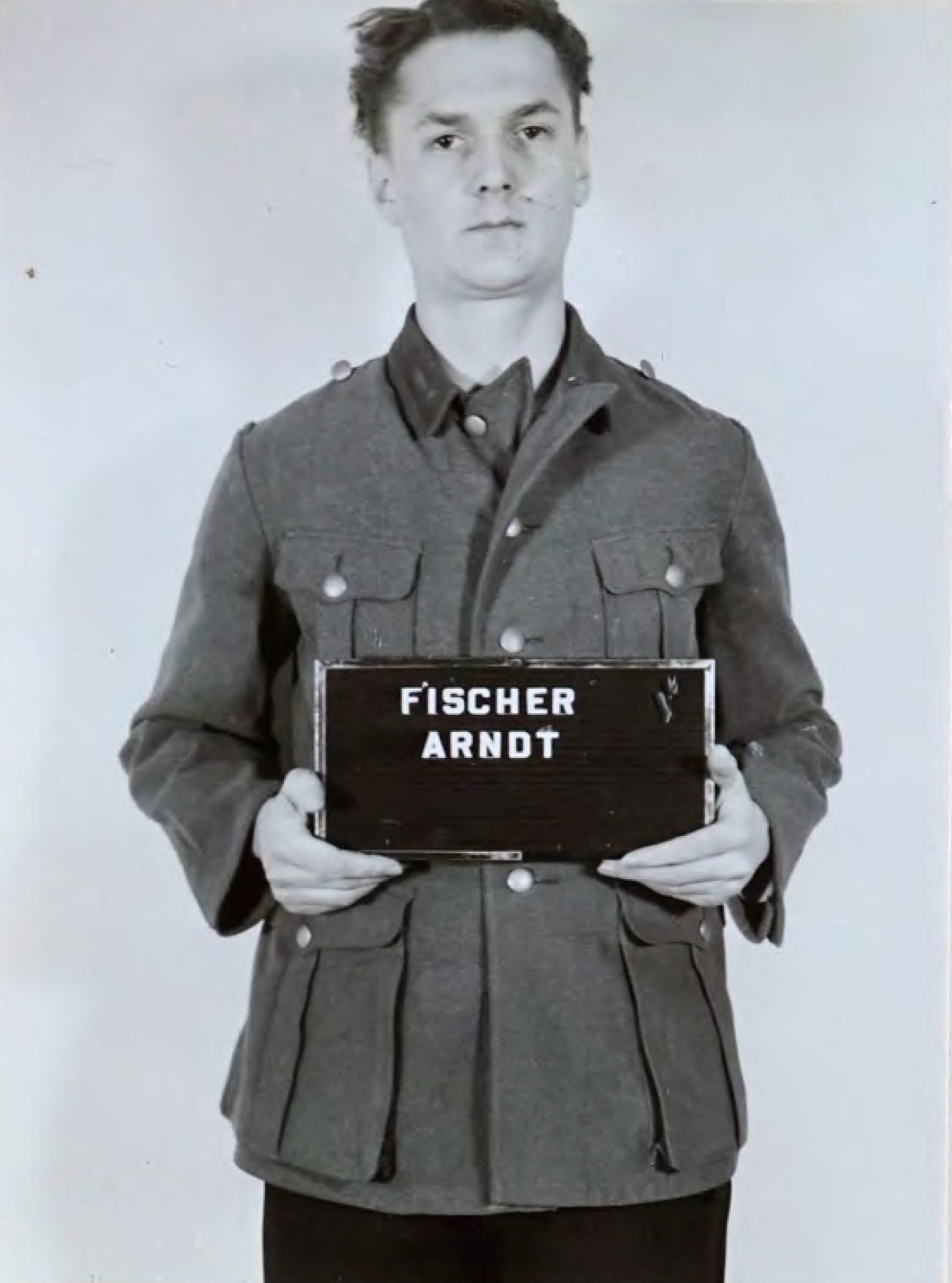

Panther 152 in Ligneuville

As the first German tank appeared— Panther 152 from SS-Panzer Regiment 1, LSSAH—it was struck by a 76mm round from the M4 Tank Dozer. Panther 152 was commanded by SS-Untersturmführer Arndt Fischer. The shell penetrated the rear armor, killing the driver, SS-Panzergrenadier Wolfgang Simon, instantly. The impact ignited the tank, leaving Fischer severely burned. SS-Rottenführer Josef Duda, the gunner, along with SS-Panzergrenadiers Gunter Weseman and Gunter Ikrat, the loader and radio operator respectively, managed to escape. Seeking cover near the Hôtel des Ardennes, Peiper’s driver halted a half-track while Peiper dismounted to assist in treating Fischer’s wounds.12

The tank was commanded by SS-Untersturmführer Arndt Fischer. The shell penetrated the rear armor, killing the driver, SS-Panzergrenadier Wolfgang Simon, instantly. The impact ignited the tank, leaving Fischer severely burned. SS-Rottenführer Josef Duda, the gunner, along with SS-Panzergrenadiers Gunter Weseman and Gunter Ikrat, the loader and radio operator respectively, managed to escape 13. Seeking cover near the Hôtel des Ardennes, Peiper’s driver halted a half-track while Peiper dismounted to assist in treating Fischer’s wounds.14

Arndt Fischer, born in 1921, had been a member of the SS since February 20, 1939, and was 23 years old during the Ardennes Offensive. After the war, Fischer was prosecuted during the Malmedy Trials, where the prosecution presented evidence that he had aided in transmitting the order to company commanders of the 1st Battalion to execute prisoners of war and Allied civilians on or about December 15, 1944. He was further accused of being responsible for such executions between December 16, 1944, and January 13, 1945. Fischer was found guilty and sentenced to 15 years in prison 15.

The Panther 152 was still there when the Americans recaptured the town, although air liaison officers—Major Albert Triers, Major William Abbot, and 1st Lieutenant Richard Zimbowski—attempted to claim it as a kill by the Ninth Air Force 17.

Frustrated by the loss of an officer he regarded as a friend Peiper attempted to take direct action. Grabbing a Panzerfaust, he moved toward the American tankdozer, intending to destroy it. Before he could reach his target, however, a round from a German tank inadvertently struck the tankdozer, disabling it 18.

The German column then proceeded to neutralize the two immobilized American Shermans and the assault gun. Recognizing the need to secure the town before advancing further, Peiper ordered SS-Panzergrenadiers to clear Ligneuville while he briefly entered the Hôtel du Moulin. There, he spent approximately half an hour consuming food left behind by Timberlake and his staff 19.

With Ligneuville under German control, Peiper turned his attention to the next phase of his advance. His objective was to reach a road west of town that led directly to Stavelot. Though this route technically encroached on the 12th SS Panzer Division’s designated sector, it provided better mobility than the road assigned to him farther south. Lacking radio communication with his divisional headquarters, Peiper assumed from the absence of significant combat noise in Malmédy that the 12th SS Panzer Division was still lagging behind. He planned to reach Trois-Ponts after Stavelot, where he would rejoin his assigned route. Trois-Ponts, named for its three bridges spanning the Amblève and Salm Rivers, was a crucial crossing point. From there, he intended to advance to Werbomont, which lay on the north-south Bastogne-Liège highway. If successful, this maneuver would allow him to bypass the worst of the Ardennes terrain and secure a relatively direct route to the Meuse River at Huy, approximately twenty-five miles beyond Werbomont 20.

Peiper’s men swiftly overran the American command post, capturing multiple officers—eight were executed on the spot. Peiper then established a temporary headquarters at Hôtel du Moulin, where his men ate, drank, and looted the surrounding area 21.

As Peiper consolidated his hold on the town, Obersturmführer Arndt Fischer’s Panther was knocked out by a Sherman during a brief skirmish south of Ligneuville. The engagement involved elements of Combat Command Reserve (CCR), 7th Armored Division, attempting to slow the German advance 22.

At the Amblève bridge, German combat engineers searched for demolition charges, aiming to cut off potential American reinforcements. A temporary ceasefire followed as both sides evacuated their wounded 23.

With Ligneuville secured, Peiper remained in the town, meeting with SS-Oberführer Wilhelm Mohnke, commander of the 1. SS-Panzer-Division, to assess the next phase of the advance 24.

The War Crimes in Ligneuville

Eight GIs from Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, surrendered and were executed—shot in the back of the neck 25.

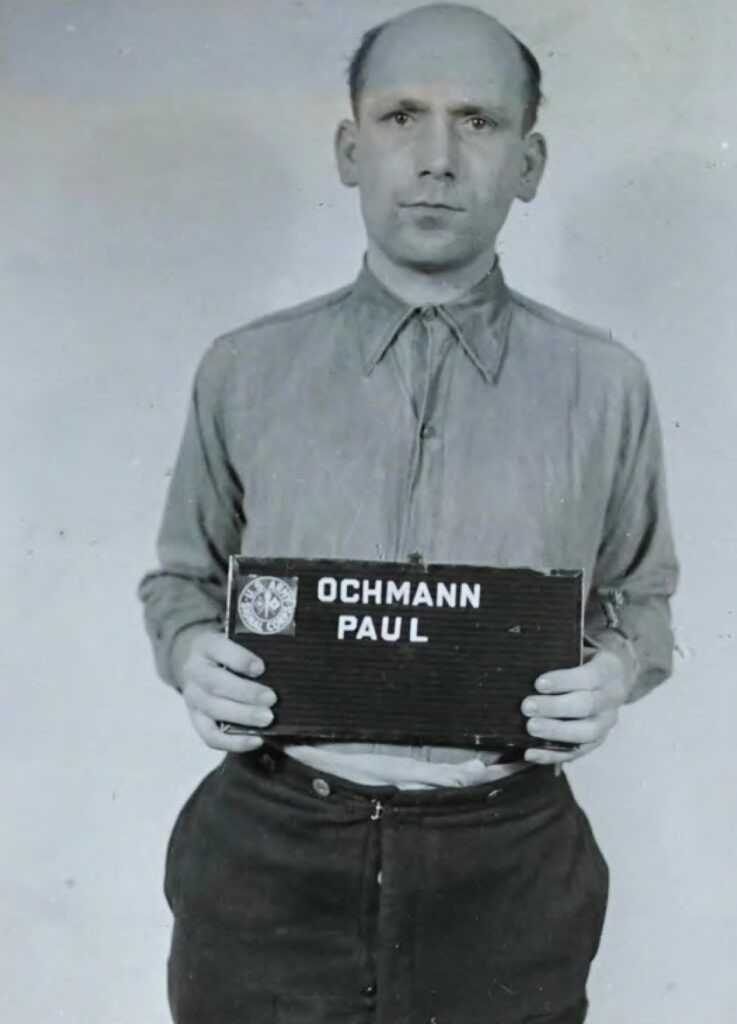

A witness, Marie Lochen, saw the events unfold. While tending her cattle, she observed about thirty captured GIs being escorted by SS men. SS-Oberscharführer Paul Ochmann and SS-Sturmmann Suess, both from the 9. Kompanie, SS-Panzer-Pionier-Bataillon 1, selected eight prisoners at random. They ordered them to march, hands on their heads, toward a path lined with an embankment 26.

Ochmann positioned them with their backs turned. The location was intentional—shots from behind would send the bodies tumbling down the slope. He executed four or five with a pistol. Suess killed the remaining prisoners using the same method 27.

At the Hôtel du Moulin, Ochmann confronted additional captives, including Captain Green. “Tuez-les!” ordered an SS officer. The hotel’s owner, M. Rupp, attempted to intervene, but Ochmann struck him repeatedly 28.

An abrupt intervention halted the executions. Another SS officer entered and ordered, “Il suffit! Laissez ces hommes en paix! À votre poste immédiatement!” Ochmann obeyed. Seizing the opportunity, Rupp rushed to the cellar and offered alcohol to the SS men. The remaining prisoners were spared 29.

22 American soldiers from the 14th Tank Battalion, 9th Armored Division,

Company B, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, 9th Armored Division, US Army

were captured and marched to the Hôtel du Moulin, which Peiper had selected as his temporary headquarters 30.

Upon arrival at Hôtel du Moulin, eight captured American soldiers were separated from the group and led to the side of the hotel. There, SS-Hauptscharführer Paul Ochmann, a 32-year-old officer from the 1. Bataillon, SS-Panzer-Regiment 1, Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, and another SS-Unteroffizier executed them.

Madame Marie Lochem, a Belgian civilian tending her cows in a nearby barn, witnessed the massacre. She saw Ochmann line up the prisoners and shoot them one by one in the head. All eight men were murdered at close range after surrendering, making this a clear violation of the laws of war.

According to later testimonies, some were forced to kneel before being shot at point-blank range, the executioners placing their pistols in the mouths of the victims.

From the kitchen window, Rupp watched in horror as SS-Hauptscharführer Paul Ochmann forced eight captured American soldiers into the yard. Without hesitation, Ochmann raised his pistol and began executing them one by one.

For years, the hotel’s owner, Peter Rupp, had lived a double life. Publicly, he catered to German officers; secretly, as “Monsieur Kramer,” he worked with the Belgian White Army resistance, sheltering Allied airmen before smuggling them through the underground network. At least 22 American, British, and French airmen owed their lives to him. On this 17 December, But Rupp wasn’t finished.

Inside the hotel, fourteen more American prisoners were being held at gunpoint, awaiting a similar fate. Thinking fast, Rupp used his reputation and his store of fine wine and cognac to distract the SS guards. As the officers drank, the executions were delayed—and eventually abandoned 31. Thanks to Rupp’s intervention, fourteen Americans survived that night.

Desperate to prevent further killings, he attempted to reason with a German NCO. Inside the hotel, fourteen more American prisoners awaited what seemed to be an inevitable fate. Realizing that direct intervention was impossible, Rupp resorted to deception. He used his reputation and stock of fine wine and cognac to distract the SS guards, delaying the executions. As the officers drank, the killings were postponed—and ultimately abandoned 32.

The victims were Staff Sergeant Lincoln Abraham (29) 33, Technician 5th Grade John M Borcina (27), Staff Sergeant Joseph Collins (32), Private First Class Michael Penney (22) 34, Technician 4th Grade Casper Johnson (25), Private Clifford Pitts (36), Private Gerald Carter (37), and Private Nick Sullivan (22). Initially, Abraham’s name was incorrectly inscribed as “Abraham Lincoln” on the memorial, but this was later corrected when the site was refurbished.

After the war, Lincoln Abraham, Gerald Carter, and Nick Sullivan were repatriated to the United States for reburial. The other five—Borcina, Collins 35, Penney, Johnson, and Pitts—were laid to rest at Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery in Belgium 36 37 38.

Today, a memorial near the Hôtel du Moulin in Ligneuville honors these eight men, victims of Kampfgruppe Peiper’s war crimes 39.

Investigation of the Malmedy Massacre

Following the war, Paul Ochmann was tried for executing American prisoners in Ligneuville. In an extrajudicial confession, he admitted to personally shooting four or five unarmed POWs in the neck while a subordinate executed the others. His confession was corroborated by Walter Fransee, a soldier from the 1. Panzergrenadier-Division, who testified that Ochmann had sought assistance in carrying out the executions. At trial, American interrogator Lt. Perl stated that Ochmann’s confession was given voluntarily, without coercion. However, posttrial statements challenged this claim. Ochmann later asserted he had been subjected to physical abuse, prolonged detention, and psychological pressure, compelling him to sign a fabricated confession. Fransee, who initially testified against him, also retracted his statement, claiming it had been obtained under duress. The Simpson Report and the Administration of Justice Review Board, which investigated the Malmedy Trials, documented instances of prisoner mistreatment during interrogations. While the Judge Advocate recommended the death penalty, the reviewing officer determined that the lack of sufficient corroborating evidence—beyond contested statements—precluded its imposition. Despite overwhelming indications of guilt, Ochmann’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment—not out of clemency, but due to legal concerns over the methods used to obtain key evidence 40.

After a two-hour halt in Ligneuville for reorganization, Kampfgruppe Peiper resumes its advance westward. The column moves unopposed through the villages of Pont and Beaumont 41 42.

Sources Ligneuville chapter:

Toland, John. “The Brave Innkeeper of ‘The Bulge’.” Coronet, vol. 47, no. 2, Dec. 1959, pp. 158–163. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/sim_coronet_1959-12_47_2_0. Accessed 16 Mar. 2025.

Pont

Evening

Kampfgruppe Peiper reached Stavelot in the late afternoon.

Stavelot

Kampfgruppe Peiper reached the outskirts of Stavelot as dusk settled over the Ardennes. The town, which had spent the day in uneasy quiet, was about to become a battleground.

Based on the personal recollections of Guy Lebeau, a young resident of Stavelot during the battle. His memories were preserved and shared through Henri Rogister 43.

Morning: Unease in Stavelot

08:00 – A U.S. roadblock is hastily established in town, with two American soldiers crouched behind a machine gun facing southwest toward Trois-Ponts. Civilians exchange nervous glances—why defend that direction when the real danger lies to the east? At the Amblève River bridge, similar positions suggest the Americans are securing key crossings, but there’s a growing sense of disarray .

09:30 – Without warning, the roadblock is abandoned. The soldiers have vanished. No explanation, no orders relayed. Stavelot is suddenly exposed 44.

10:30 – U.S. tanks appear, rumbling through town toward Trois-Ponts. The movement is constant—7th Armored Division units pushing forward, their crews grim-faced. To some, it looks like reinforcement; to others, a prelude to retreat 45.

Afternoon: The Exodus Begins

14:00–17:00 – The Stavelot garrison begins to dissolve. These are not frontline troops—logisticians, engineers, and military police—now hastily evacuating. Whispers spread: German paratroopers may have landed west of town. Fear tightens its grip 46.

Evening: The Last Warning

18:00 – Refugees stagger in from the east, faces drawn with exhaustion. “The Germans are coming.” Burgomaster Arnold Godin wastes no time—he orders a curfew. Doors are bolted, windows shuttered 47.

20:00 – More troubling reports: German forces have reached Lodomez. Civilians, sensing the inevitable, descend into cellars with whatever they can carry—mattresses, blankets, food. The walls of their homes will be their last line of defense 48.

Nightfall: The Silence Before the Storm

Distant gunfire cracks through the night. No one knows where it’s coming from—or how soon it will reach them. In the cellars of Stavelot, sleep is impossible. The battle is coming

Throughout the day, Stavelot remains calm. However, after Sunday mass, engine noises are heard as American armored vehicles from the 7th Armored Division move through town toward Trois-Ponts.

Kampfgruppe Peiper reached the outskirts of Stavelot as dusk settled over the Ardennes. The town, which had spent the day in uneasy quiet, was about to become a battleground.

08:00 – A U.S. roadblock is set up in Stavelot, with two GIs manning a machine gun positioned toward Trois-Ponts (southwest). The placement raises concerns among civilians, as the frontline is to the east. Similar defensive positions are reported at the Amblève River bridge, suggesting that roads from Malmedy and Francorchamps may have been similarly secured 49.

Morning: Unease in Stavelot

08:00 – A U.S. roadblock is hastily established in town, manned by two GIs with a machine gun facing southwest toward Trois-Ponts. Civilians exchange nervous glances—why defend that direction when the real danger lies to the east? At the Amblève River bridge, similar positions suggest the Americans are securing key crossings, but there’s a growing sense of disarray 50.

09:30 – The roadblock is abandoned, and the GIs are gone 51.

10:30 – U.S. tanks arrive, moving toward Trois-Ponts from Francorchamps and Malmedy. The 7th Armored Division passes through the town continuously throughout the day 52.

14:00–17:00 – The Stavelot garrison, composed mostly of non-combat support units (logistics, engineering, maintenance, military police), begins evacuating. Reports indicate that German paratroopers may have been dropped west of Stavelot, heightening concerns among civilians 53.

18:00 – Belgian refugees arrive from the east, warning that German forces are returning. The Burgomaster, Arnold Godin, imposes a curfew 54.

20:00 – Reports emerge that German troops have reached Lodomez. Civilians prepare for an extended stay in cellars, bringing mattresses, blankets, clothing, and food 55.

Evening – Gunfire is heard in the distance, increasing anxiety among residents. Civilians struggle to sleep, uncertain about the unfolding situation 56.

09:30 – Without warning, the roadblock is abandoned. The soldiers have vanished. No explanation, no orders relayed. Stavelot is suddenly exposed 57.

Afternoon: The Exodus Begins

10:30 – U.S. tanks appear, rumbling through town toward Trois-Ponts. The movement is constant—7th Armored Division units pushing forward, their crews grim-faced. To some, it looks like reinforcement; to others, a prelude to retreat 58.

14:00–17:00 – The Stavelot garrison begins to dissolve. These are not frontline troops—logisticians, engineers, and military police—now hastily evacuating. Whispers spread: German paratroopers may have landed west of town. Fear tightens its grip 59.

Evening: The Last Warning

18:00 – Refugees stagger in from the east, faces drawn with exhaustion. “The Germans are coming.” Burgomaster Arnold Godin wastes no time—he orders a curfew. Doors are bolted, windows shuttered 60.

20:00 – More troubling reports: German forces have reached Lodomez. Civilians, sensing the inevitable, descend into cellars with whatever they can carry—mattresses, blankets, food. The walls of their homes will be their last line of defense 61.

Nightfall: The Silence Before the Storm

Distant gunfire cracks through the night. No one knows where it’s coming from—or how soon it will reach them. In the cellars of Stavelot, sleep is impossible. The battle is coming.

In the afternoon – U.S. engineers set up roadblocks south of Stavelot in anticipation of the German advance.

16:30 – Kampfgruppe Peiper arrives at Stavelot, attempting to cross the Amblève River.

The bridge over the Amblève River was still intact, making it a vital crossing point.

18:30 – Sergeant Hensel from the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion installs a minefield on the Corniche road leading into Stavelot.

19:30 – The roadblock is attacked by German infantry, possibly supported by tanks. Hensel and his men retreat.

First attack on Stavelot:

Peiper’s lead tanks moved into town but encountered fierce resistance from American troops.

The 291st Engineer Battalion and elements of the 30th Infantry Division fought house to house.

The bridge was nearly lost, but American forces held on.

Peiper’s unit stalled in Stavelot for the night, unable to secure the river crossing .

21:00 – Hensel reaches La Gleize and reports the attack, but his warning is not acted upon immediately.

22:45 – U.S. high command is notified of the imminent threat to Stavelot, but no immediate defensive actions are taken.

Monday, December 18, 1944

Investigation of the Malmedy Massacre

As the Battle of the Bulge concluded with a German defeat, Allied forces launched investigations into the massacre of American prisoners of war. Early inquiries identified Kampfgruppe Peiper as the unit responsible for the Malmedy massacre, though its personnel were dispersed across prison camps, hospitals, labor detachments, and even the United States62.

Challenges in Interrogation

Investigators quickly encountered difficulties in questioning the accused, as inadequate security in prison camps allowed suspects to rejoin their comrades and coordinate their statements after interrogation63. It was also discovered that before the Ardennes Offensive, SS troops had been sworn to secrecy regarding orders to execute prisoners of war64.

To improve interrogation effectiveness, all Kampfgruppe Peiper members were transferred to an internment camp at Zuffenhausen, but initial barracks-style housing still allowed communication between prisoners, further complicating the investigation65.

The Blame on Major Poetschke

During this period, evidence emerged that Joachim Peiper had instructed his men to blame the Malmedy massacre on Major Werner Poetschke, who had been killed in Austria during the war’s final days. Peiper’s subordinates carefully followed this directive, making it difficult to assign individual responsibility66.

Interrogation at Schwäbisch Hall

To ensure strict isolation during questioning, key suspects were relocated to the Schwäbisch Hall interrogation center, a modern German prison where detainees were kept in individual cells67. The initial transfer included over 400 prisoners, with additional transfers continuing through March 194668.

It was during interrogations at Schwäbisch Hall that allegations of prisoner mistreatment emerged, later influencing the legal proceedings of the Malmedy Trials69.

Source: 70.

Footnotes

- Cuppens, Gerd. Massacre à Malmedy ? Ardennes : 17 décembre 1944. Le Kampfgruppe Peiper dans les Ardennes. Éditions Heimdal, 1989

- Grégoire, Gérard. Les Panzer de Peiper face à l’U.S. Army. Stavelot: J. Chauveheid, 1986.

- William Morris Hoge (13 January 1894 – 29 October 1979)

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- Bergstrom, Christer. The Ardennes, 1944-1945: Hitler’s Winter Offensive. Casemate / Vaktel Forlag, 2015

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- Cuppens, Gerd. Massacre à Malmedy? Ardennes: 17 décembre 1944. Le Kampfgruppe Peiper dans les Ardennes. Éditions Heimdal, 1989.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- Bergstrom, Christer. The Ardennes, 1944-1945: Hitler’s Winter Offensive. Casemate / Vaktel Forlag, 2015.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- Parker, Danny S. Fatal crossroads: the untold story of the Malmédy Massacre at the Battle of the Bulge. Da Capo Press, 2012.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- United States. War Department. Malmedy Trial: Volume 7, Appendix B-F. U.S. Military Legal Resources, Library of Congress, maint.loc.gov. Accessed 16 Mar. 2025

- “Panther Ausführung G with Tactical Number 152 of SS-Panzer Regiment 1, Kampfgruppe Peiper.” The King of La Gleize, 2019. Facebook post. .

- “Panther Ausführung G with Tactical Number 152 of SS-Panzer Regiment 1, Kampfgruppe Peiper.” The King of La Gleize, 2019. Facebook post. .

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. 1st ed., Morrow, 1984.

- Gillet, 2003.

- Gillet, 2003.

- Gillet, 2003.

- Pallud, Jean-Paul. Ardennes, 1944: Peiper and Skorzeny. Elite Series 11. London: Osprey Publishing, 1987.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: hiver 1944-1945. Ed. Racine, 2006.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: hiver 1944-1945. Ed. Racine, 2006.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: hiver 1944-1945. Ed. Racine, 2006.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: hiver 1944-1945. Ed. Racine, 2006.

- Longue, Matthieu. Massacres en Ardenne: hiver 1944-1945. Ed. Racine, 2006.

- Liberation Route Europe, www.liberationroute.com/pois/1857/memorial-to-the-murdered-us-soldiers-lingneuville

- Source: “The Brave Innkeeper” – World War Media https://www.worldwarmedia.com/2016/09/15/thebraveinnkeeper/

- Source: “The Brave Innkeeper” – World War Media

- https://fr.findagrave.com/memorial/11478645/lincoln-abraham

- http://wartimeheritage.com/whaww2ns6/wwii_penney_michael_bernard.htm

- D, Row 15, Grave 33

- Liberation Route Europe, www.liberationroute.com/pois/1857/memorial-to-the-murdered-us-soldiers-lingneuville

- MacDonald, Charles B. A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. New York: Morrow, 1984, p. 228

- Traces of War, www.tracesofwar.com/sights/982/Memorial-US-9th-Armoured-Division.htm

- Traces of War, www.tracesofwar.com/sights/982/Memorial-US-9th-Armoured-Division.htm

- United States. War Department. Malmedy Trial: Volume 7, Appendix K-P. U.S. Military Legal Resources, Library of Congress, maint.loc.gov. Accessed 16 Mar. 2025.

- Pallud, Jean-Paul. Ardennes, 1944: Peiper and Skorzeny. Elite Series 11. London: Osprey Publishing, 1987.

- Heyden, 2021

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- Lebeau, Guy. “Tristes souvenirs… Stavelot, Hiver 44.” Histomag 44, no. 59, avril 2009, Association Remember 39-45.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes. Investigation of the Malmedy Massacre. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949, p. 2.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 3.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 5.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 6.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 7.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 8.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 9.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes, p. 10.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on War Crimes. Investigation of the Malmedy Massacre. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949. Available at: tile.loc.gov